Cone of Inspiration

When Redford built a concrete cone-shaped structure in 1933 to house his Native American artifacts collection, there were very few motels alongside US highways. He added six similar cones in 1935 to serve as tourist cabins, and his motel enterprise was off to the races. In fact, the very word “motel” had been coined only ten years earlier, and only because of space consideration on a sign.

“The word ‘motel’ originated in California with the ‘World’s First Motel’ in San Luis Obispo, when the Motel Inn was established in 1925. A combination of the words motor and hotel, the motel is a hotel (typically single story) designed for patrons traveling by car,” said Heather David, author of Motel California. “Because motels catered to a car culture, the primary form of advertising was roadside advertising - with eye-catching features such as distinctive architecture, neon signage, and in later years, swimming pools strategically positioned near street view.”

While roadside architecture eventually adopted the vernacular style in each region, there was little done to stand out among the small but growing number of competitors. Redford had a plan though, and he threw down the gauntlet. His conical-shaped cabins were a whimsical nod to Native American abodes, as well as the onset of kitsch as king on the open road. In doing so, he unwittingly left behind a legacy of pure Americana.

That year those six cabins became the first of seven Wigwam Villages (he preferred “wigwam” over “teepee”). This first unit was located in Horse Cave Kentucky on US 31E, one strand of the Dixie Highway. The DH, brain child of Carl G. Fisher, carried an increasing volume of traffic to Florida, and thus provided immediate benefit to Redford’s modest enterprise.

Richard Ratay, author of Don’t Make Me Pull Over! An Informal History of the Family Road Trip, acknowledges that motel architecture was not something that happened from the first day. “Initially, there was no architecture. During the first road travel boom during the 1920s, motorists simply found a pleasant place along a road, pulled over, and either set up tents or just slept in their cars. It was called ‘autocamping.’ Eventually, enterprising businessmen improved on these campsites by building ‘motor courts,’ which were basically groups of huts built in a horseshoe shape around a fire pit or central common area. These huts offered only basic amenities, perhaps a couple of cots and a stove. The Wigwam Villages built by Frank Redford during the 1930s were really just fancy versions of these motor courts,” he continued. “Redford settled on the Indian theme because he owned a museum/gift shop that sold Native American artifacts and [he] wanted to extend that theme to his new lodging facilities.”

Redford applied for a patent for his design in 1935, and received it in 1936. Each tipi had a diameter of 14 feet, rose 32 feet from the ground, included a small partitioned bathroom area, and featured a somewhat protected entryway mimicking fold-away flaps of a real tipi. The patent was Redford’s green light to increase his operations, which he intended not to be an ownership chain, but rather with franchisees. This, too, was an innovation, as by that time, the Alamo Plaza Hotel Courts in Texas was the only chain on the horizon, it being centrally owned.

Never mind that Redford misappropriated the word “wigwam,” because the units were in fact more teepee-like. Teepees (purists will argue “tipi” is more accurate) are portable tent-like dwellings, which Redford’s resemble, whereas wigwams are small cabins with its frame covered in bark or skins. Adding a little more comedy is the fact that wigwams were the domain of eastern tribes, and thus nowhere in Redford’s geographic coverage would a real wigwam have ever been found.

Redford’s indiscretion, though, was not of any concern for tourists. “There sure wasn’t any disconnect for travelers. They weren’t looking for historical accuracy. They were looking for an interesting place to spend a night or two and take a fun memory home with them,” said Ratay.

David argues that motel operators took liberties not to mislead, but rather to fuel travelers’ flight from reality. “Motel theming was always more about fantasy than reality. There was a considerable amount of creative license when it came to these themes. Sure, there are/were plenty of historical and geographical inaccuracies, but I don’t believe that motel owners intentionally misled people,” she said. “The idea was to offer everyday people an opportunity to escape.”

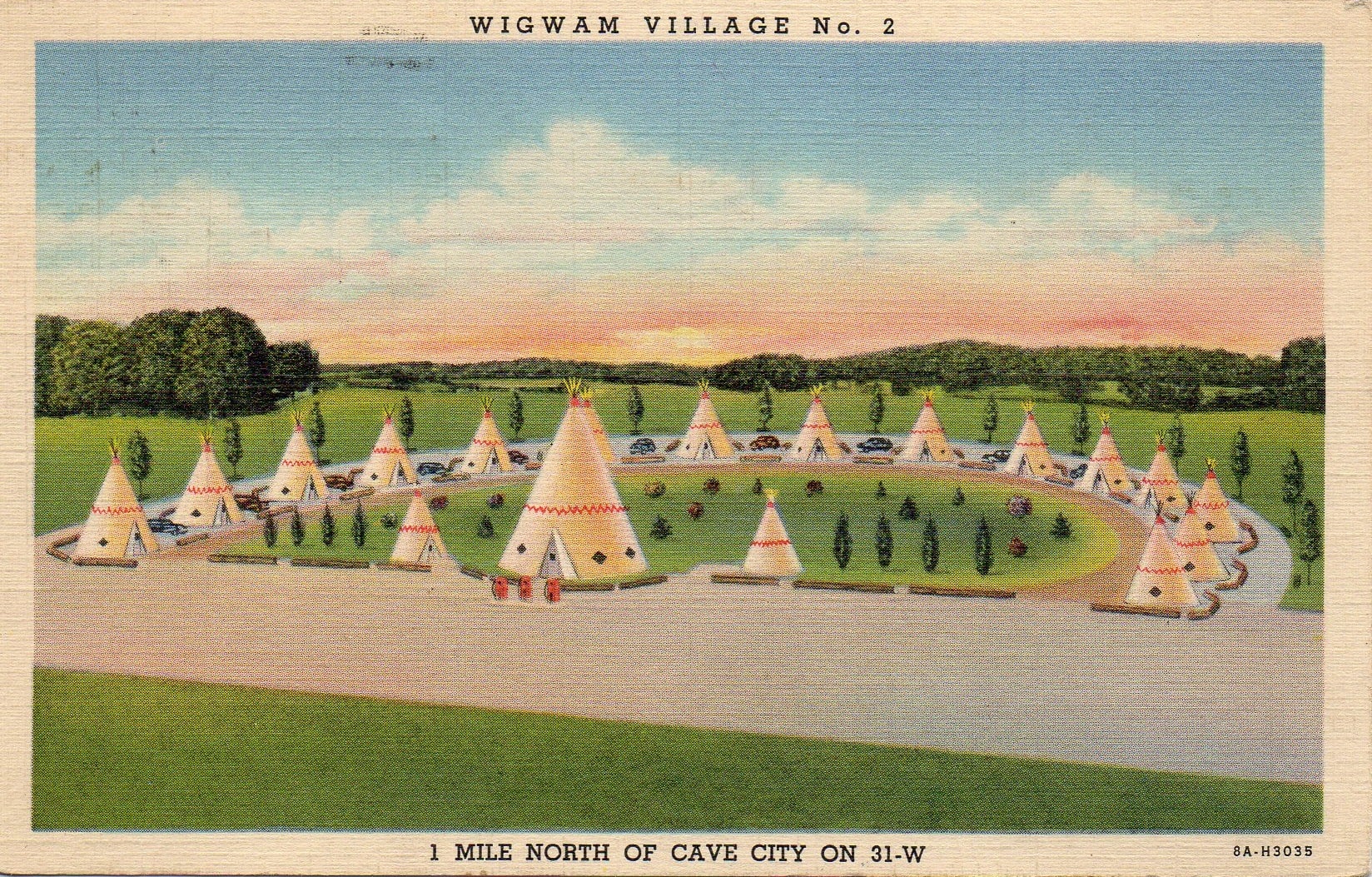

Redford closed Village #1 in 1937 because he felt the state was more likely to develop and maintain nearby US 31W. He thus opened Village #2 a few miles down the road in Cave City. The original operated under new owners and different names until it closed; it was demolished in 1982. Village #2, which is still operating today, has 15 teepees in a semi-circle, with a larger structure in the center that once housed a restaurant. Today, it serves as the office and a gift shop. Sahudir Mir and his wife have owned the Cave City property since 2005.

The Great Depression no doubt hindered Redford’s ability to grow his business, as it wasn’t until 1940 that two more Wigwam Villages were added. Village #3 was planted in New Orleans on US 61, while Village #5 (it is unknown why they went out of sequence) sprouted in Bessemer, Alabama, on US 11. The New Orleans location only made it to 1954, while Bessemer’s managed to keep afloat until 1964.

World War II interrupted expansion plans once again, dealing an eight-year drought, while the nation committed resources to the war effort. Travel and tourism were down anyway, and Redford had to wait patiently to see his dream unfold. Once things settled down, he continued the trend of focusing on north-south US highway corridors, opening Village #4 in Orlando, Florida, on US 441 in 1948. It had 27 teepees, the largest in the chain.

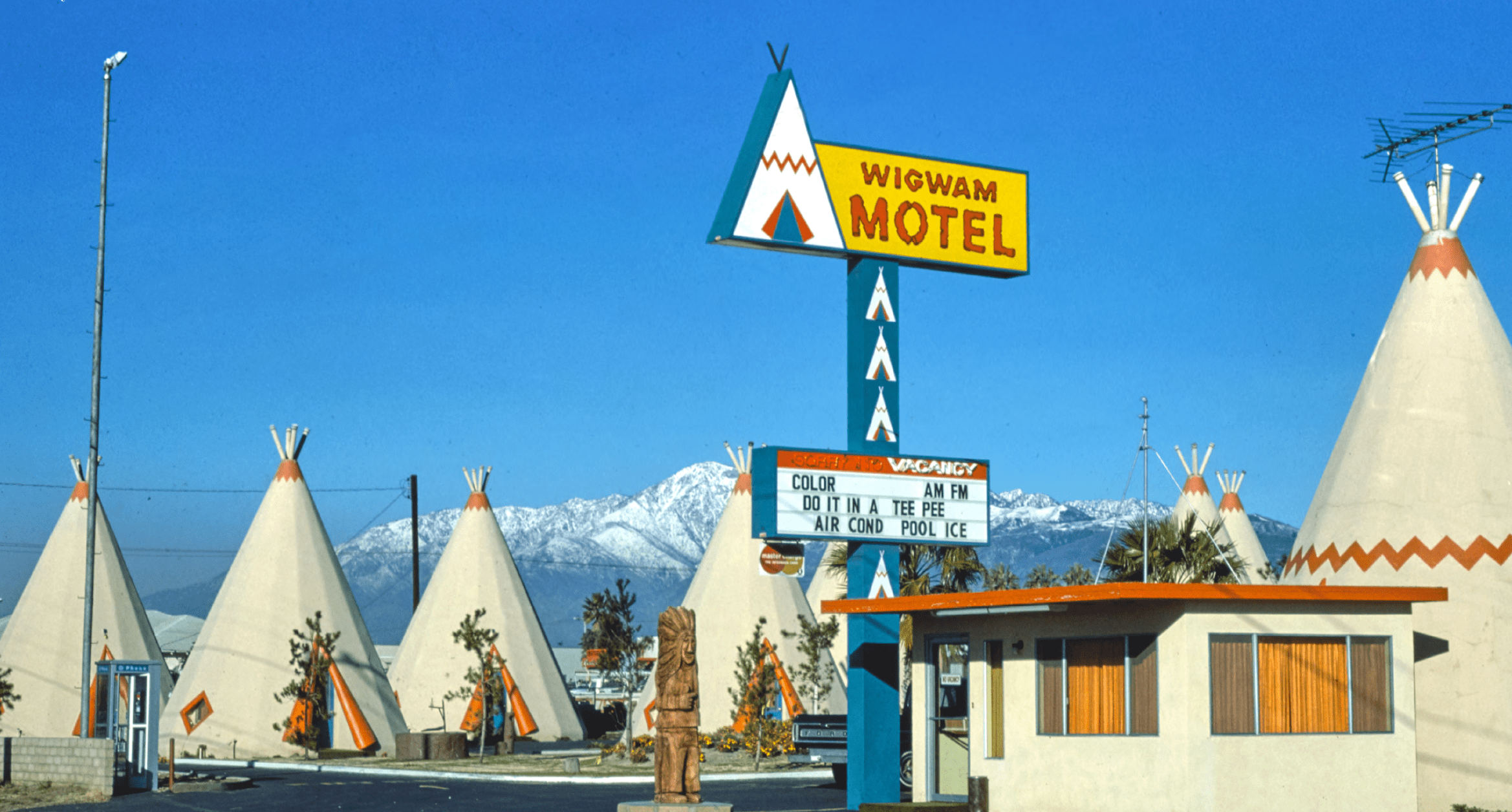

The post-war boom brought a change of heart to Redford, who then turned west for his final expansion. Village #7 (once again out of sequence) opened in 1949 in San Bernardino, California, while Village #6 was built in sunny Holbrook, Arizona. Both are along US Route 66, which by then was carrying a heavy volume of travelers on holiday or seeking fame and fortune on the west coast. The Holbrook and San Bernardino locations join Cave City as the only remaining Villages still in operation. They are also family-owned businesses. The Lewis family has operated the Holbrook site throughout its existence, while the Patel family has owned the San Bernardino location since 2003. Redford had originally built the California location to manage himself.

At that point, Redford’s chain grew no more. There had been a few knock-off competitors, like the one in Wharton, Texas, seeking to infringe on his design and theme, but there were other changes afoot, ones that likely dealt more of a punch than copycats. Redford’s Wigwam Villages were, by concept, intended more as novelty than basic functionality. With no more than 19 units per village, the Wigwams were increasingly being outdone in capacity by emerging mom-and-pop motels with sprawling properties that had 30 or more rooms. And, unknown to Redford at the time, the onset of large corporate motel chains like Holiday Inn, Ramada Inn, and Howard Johnson were about to redefine the hospitality industry.

These changes signaled new preferences for larger accommodations, and subsequently, the predictability of the larger chains. Each teepee was about 154 square feet in area, while standard rectangular motel rooms were trending ever larger (they now average 325 square feet today). In high-growth areas like New Orleans and Orlando, the land beneath the wigwams became more valuable than the structures on top.

And Then the Decline

Redford’s grand project began to lose its relevance as the 1960s arrived, primarily as a new generation of travelers evolved. What was “kitschy-kool” in the 1930s through 1950s lost its luster as the happy-go-lucky 1950s and 1960s ushered in a completely new era of roadside attractions that were much larger and even quirkier in scope. Themed motels featuring exotic places and the forthcoming space age replaced the earlier fascination with the southwest and Native American culture.

Further complicating matters were the large chain motels, and a growing preference among travelers for predictability. While nowadays there is an emerging interest in seeking out a unique and unexpected experience, at the time, travelers wanted more control over their dining and lodging. There was little doubt in anyone’s mind that a room at a Holiday Inn in Florida was the exact same as one in California, a trend that was felt in the restaurant industry as well.

Worse yet, the Wigwams fell into disrepair as prior management lost interest in maintaining their properties. With shiny, new alternatives at the freeway exit as opposed to the old road, it became an easy choice for motorists to shun what was once cool, but had begun looking a little long in the tooth. Adding insult is that some of the wigwams became known as no-tell motels, the deciding blow that turned families away.

It would take the onset of the 21st Century and nostalgia-seeking Baby Boomers to signal a revival in interest of these period-piece survivors.

Making New with Old

Managing properties that are between 70 and 82 years of age has been no small task for the current owners of the wigwams. If anything could go wrong, it has done so at least once already, and often at great expense.

Mir recalls the distressed condition of his Cave City property when he bought it 14 years ago: “It was in pretty bad shape. The electric lines, the water lines, the furniture were in bad shape. It was really filthy.” But he and his wife had come to America in search of opportunity, and like many Indian immigrants, bought a motel. “This is a family business. I got here to America in 2004, and I was looking for something to do.”

Being recent immigrants, Mir had no clue of the historical significance of the wigwams, nor of what was about to happen when Cars was released in 2006. “When we bought it, it was like any motel. We did not know the value of the motel. But I learned when people came by and told me. They came in asking for an interview. So then I learned that it has a different kind of value to people all over the country and world. Year after year. I had to dig out the history and found it is a landmark of American history.”

Luck had landed in his lap.

In the time that Mir has owned the Cave City, Kentucky, location, he has put a lot of work into repairing and upgrading the facilities. “We have done a lot of renovations and daily work. We have done a thorough cleaning, we have done work outside, we have fixed the furniture, we have done work on the electric lines. We have all new plumbing inside and new beds and all kinds of stuff,” he said with pride.

During the post-Cars era, Mir has come to learn a little about American pop culture and the appeal of nostalgia, something that is certainly an alien notion for someone who did not experience it when it happened. Today, he welcomes nostalgia seekers, and understands the appeal. “Actually, there are many people who come here for this reason, and they come every year. They spent their honeymoon here, and now they bring their grandkids. They talk about it being a unique motel. People bring their kids and sleep in a tipi.”

If anything, the warm glow of nostalgia has overtaken Mir, and he now seems to cherish what he unknowingly bought in 2005. “A lot of good people come, they come to talk to me, and invite me to be their friend. Some people have this as a bucket list item. Some families have been coming for 30-40 years.” And to help ensure that Wigwam Village #2 is around for future generations to enjoy, Mir is working to maintain the property. “We have some plans to do a little bit more work, but we are looking for a government grant. If we can get that, we can do much more,” he said, indicating he hopes to leverage his historical status to help fund his preservation efforts.

Samir Patel’s family faced a similar challenge when his parents, Jagdish and Ramila, bought the San Bernardino property in 2003. The neighborhood had gone bad, and the motel had gained a reputation where rooms could be let by the hour. A large sign at the entrance proclaiming, “Do It In A Teepee” did not help matters.

Absentee owners had allowed the property to slide by virtue of leasing it to managers who neither cared nor had authority to make changes. “It really did take a turn for the worse, and because it went through different people who did not have the idea that this was a piece of history, that’s when the whole hourly stuff started. If my dad [hadn’t] purchased the place, the city of San Bernardino was going to tear it down,” Patel recalled.

The elder Patel set out to saving the wigwams, enlisting the help of his wife, three sons, and daughter. “You name it, we did it. Asphalt. Lawn work. We redid the pool. It was a swamp pretty much. New pumping engine. New carpet, furniture, water heaters, fixtures, sinks, toilets. We painted it, put in a laundry facility with a new washer and dryer, and rewired the whole property underground. Pretty much everything from A to Z, we did. We took over in September 2003, and finished near the end of 2005,” said Patel.

But unlike Mir, who had no idea of the historic value or the pop culture add-on about to happen, the elder Patel had long taken it to heart ever since immigrating from India. “They came to San Bernardino and have lived here since 1979. That’s why this place always caught my dad’s eye, because he lived right down the street. This is something we would pass by every day,” Patel continued.

It took a while for Samir and his siblings to understand and embrace the idea of owning a roadside attraction. “My dad’s really into nostalgic stuff. Prior to buying it he used to come here to talk to the person who leased it. ‘One day I’m going to buy this property, and it’s going to be something.’ He was the only one in the family who saw what this could be,” Patel beamed. “He had it in his mind; it was his mentality. Now that I’ve grown up and realized a lot of things, I definitely understand the significance of this property.”

The elder Patels are now up in years. Although they still stop by almost daily to tinker and toil for a few hours, they have ceded the bulk of operations to Samir, the youngest of the four kids. “My parents have not retired, but they want to soon. This business means a lot to him personally, and I don’t see [my dad] walking away. My goal is to be here in the long run and to manage this property, to keep it in the family. I want to expand on this.”

While the Pixar people did visit the California wigwams, it was the Holbrook location on which they based the movie depiction. Still, the Cars effect has been significant for all of the remaining venues. “It feels great. That Pixar movie really kicked off our reservations, especially with children. After the movie we had people come from the local areas: ‘My kids want to stay in a Cozy Cone.’ In the peak season, we have kids come in every day who want to stay in a Cozy Cone.”

Having now adopted his father’s passion for nostalgia and the historic value of the property, Samir and his parents have committed together to continually maintaining and upgrading their 19 tipis that sit beside Route 66. “We have a lot of other major work that needs to be done. Plumbing is the number one issue right now. We also want to remodel the interior of each unit. We want to future-proof it in a way so that it will last another 70 years.”

With owners like the Patels and Mirs at the helm, there is little doubt these roadside relics will indeed be around for future generations to enjoy, as well as their nostalgic parents and grandparents.

The Need for Nostalgia

Today, motels like the wigwams are roadside oddities that have become attractions in their own right. Whereas sixty years ago, they tugged at parents and kids alike for their uniqueness and novelty, it is that same novelty with a nostalgia cherry on top that is issuing the clarion call now. In a sea of generic saccharin rectangular motels surrounding freeway exits, these three relics provide something different.

“We live in a pretty homogenized world. These days, one motel is pretty much just like any other,” Ratay summarized. “The Wigwam Villages remind us [that] there was once a time in America when lodgers sought to offer travelers something more than a pleasant stay. They wanted to provide a unique experience that might never be forgotten.”

“The golden age of the motel in the U.S. was circa mid-1950s to early-1960s. I suspect that a good number of motel patrons today are looking for novelty. I first experienced motels as a child in the 1970s, when motels in the U.S. were on the decline,” David recalled. “For me, sleeping in a ‘wigwam’ was not only new and unusual, it was magic, like stepping back in time. In the 1950s and 1960s, motel owners (and especially those in states with high rates of tourism) were challenged with a highly competitive market. Theming became a marketing differentiator. In the 1960s, for example, there were over fifty motels around the perimeter of Disneyland. The majority of these businesses were privately owned mom and pop enterprises,” she continued. “With this kind of competition, what does one do to stand out from the others? The lands inside the gates of Disneyland extended to the streets of Anaheim with motels like the Princess, Alpine, Jolly Roger, and Space Age Lodge. You might not be able to afford a trip to Hawaii, but you could stay at the Waikiki Motel. You might not ever visit Egypt, but you could ride the ‘true to life camel’ at the Pyramid Motel.”

“Back in what I call the Golden Era of the Family Road Trip—the 1950s through the 1970s—novelty was extremely important. Competition among lodging operators to attract guests was fierce,” Ratay echoes. “There’s a reason well-traveled highways like Route 66 were lined with outlandishly themed motels and blinking neon people attractors—signs shaped like giant rockets, aliens, wagon wheels, buffalo and more. Motel owners would do just about anything to entice travelers to choose their operation over the guy down the road.”

That two of the three remaining Wigwam Villages are along Route 66 have not been lost on motel historians nor travelers. These were the last two Redford developed, and signaled a shift in geographical focus in the US. As far as tourism goes, the west was won a motel at a time, and Redford didn’t want to miss out on the action. Their value today along the Route is significant, their quirkiness a lightbulb for moths motoring along the Mother Road.

“Travelers along Route 66 are looking for memorable experiences and ways to connect with the rich legacy of the Golden Era of the American Road Trip. A night’s stay at a Wigwam Village allows them to get both,” said Ratay. To that end, the Holbrook wigwams, at some point, added neon signage beckoning travelers come hither, going so far as to remove signage inviting people to the museum that still exists today.

Scott Piotrowski, President of the California Historic Route 66 Association, knows the value of the wigwams in his state: “The Wigwam Motel in San Bernardino is one of the key attractions along Route 66 in California. Along with places like El Garces, Casa del Desierto, three Route 66 museums, and the Aztec Hotel, the highway in California is littered with landmarks worth seeing. What sets the wigwams apart from the rest, however, is [their] photographic appeal.”

Looking Down the Road

“The American motel as a building type both peaked and declined in the 1960s. The motel chain trend began decades ago, as well as the trend to build multi-story properties. However, another trend started in the 1990s, the boutique hotel concept, the roadside motel re-imagined. All over the country, old motel properties are being lovingly restored, as people look to escape their everyday lives and check in to the American motel experience,” David explained.

Ratay is a little less certain, but nonetheless upbeat: “Of course, it’s hard to say. I only hope we recognize the value in supporting and preserving these important landmarks of the Golden Era of the American Road Trip, which also include the classic diners, roadside attractions, rest areas and more. They’re magic portals that allow us to step back in time and experience a uniquely quirky, vibrant and exciting period in America’s history. If the reason we travel is to create lasting memories, I can’t think of a better way to do it than to pay these places a visit.”

Time and health were not on Redford’s side, though. While he pictured his San Bernardino property to be a pseudo-retirement, he took ill and had to sell by the late-1950s. He died shortly thereafter in 1957, and is buried in Horse Cave, Kentucky, not far from his original motel.

Redford started something uniquely different 86 years ago, when the motel was still a fairly new concept and road travel for leisure was just beginning. He went far out on a limb to create an experience that was different from what the small but growing number of motel operators had offered the traveling public. While those early motorists were still embracing the idea of an affordable overnight room, Redford was quick to stretch the concept into something memorable and unique. He no doubt raised eyebrows as an innovator of roadside kitsch, but soldiered on nonetheless to set himself apart from the rest. It was as if he almost knew that his brainchild would live to see another century, to be iconized in film and to delight travelers for years to come.