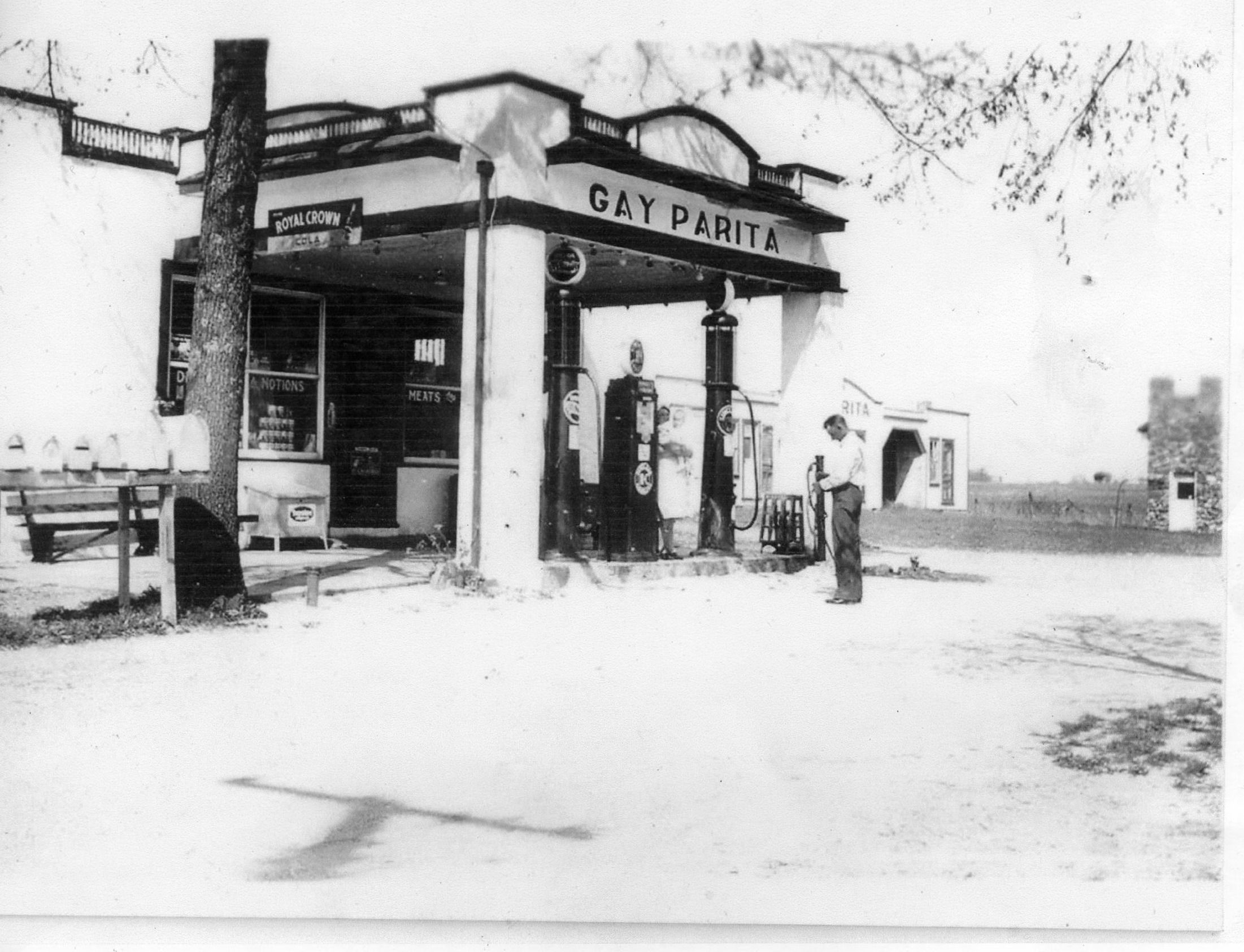

If it feels like a slice of American pie, the only thing missing is a bowl of ice cream. Or a replica 1930 Sinclair fueling station.

Wait. They’ve already got one of those.

“Well, my brother-in-law sold me this property. There was an old gas station here. We built a new gas station. The original station was built in 1930, and burned down in 1955. This property is called Gay Parita,” the late Gary Turner said in 2012, with his signature gravelly voice.

“It was built by Gay and Fred Mason. Gay Parita was named after Gay. If you were in Spain, ‘Parita’ means equal. But you only see Gay’s name up there, so she’s probably more equal than Fred was.”

Never mind that “Parita” is not exactly “equal” in Spanish (more likely Italian), and that Parita may very well have been an old place name for this part of rural Missouri about 20-miles west of Springfield. It’s all part of the myth and legend of a man who turned his retirement years into a memorial period that have left a permanent impact on the Route 66 community.

“Route 66 has a spirit. It’s alive, and it’s growing all the time.”

Even in death, his spirit is helping fuel that flame.

The Back Story

What started out as a way to stay occupied during retirement turned into what were often 16-hour days spent welcoming travelers, and serving a slice or three of fresh watermelon. If that sounds a bit like a job, you might be right, except that for Gary Turner, being the center of attention drew upon his early days as an entertainer in California, and he relished in it.

At least that’s what was put on one of his kids’ birth certificates. More on that later.

It was around 2005, as recollected by Barb Turner Barnes, Gary’s last born, that her uncle Steve and cousin Stevie erected the now-iconic replica of a vintage Sinclair service station. The real one had been built on the same location near Paris Springs, Missouri, on Route 66, and had burned down a half-century earlier. It was to become Gary’s combination mancave and Route 66 Visitors Center. Even though he had retired from the workforce, he just couldn’t sit still.

“I think it was just another of my dad’s things that he did. He always did something different. He owned his own car lot. He worked at Redi-Mix. He worked at Knott’s Berry Farm. This was his next adventure. He was always looking for his next adventure, that’s what mom would say,” Barb noted.

“I knew him right from the get-go,” said author and Route 66 historian Michael Wallis. “I think a lot of people were surprised who met him there. He had been there a relatively short amount of time, but it felt like he had been there forever. That was part of Gary, his personality, his demeanor, his manner in dealing with people. He was a man who obviously had never met a stranger. Maybe he was there before, maybe he was some old soul who came back, because he felt like it.”

The station was built as a close replica of the albeit somewhat larger original. “It’s always been Sinclair gas. They used to live in the back of the station, until they built the rock house we live in now. That was Gay Mason’s dream house. They used to have cabins here. They sat over where the garage is now,” Gary recalled.

Gary and Michael spent hours in the shade, reflecting on anything and everything. “We were totally simpatico in many ways, even politics. We had a good time. We would skewer politicians and talk about many things other than the road itself. That was the perfect venue,” Wallis continued. “It is such a road of democracy, such a human road. It’s a road for blue bloods and rednecks. It’s a couple of blue states bookending a bunch of red states, so the color runs purple.”

It didn’t take long for the station to become covered in old signage, the adjacent land to be decked out with the ephemera of the ages, from old cars to bicycles, and everything in-between. A pavilion was added behind the station (invariably where the watermelon feasts were held), and the large stone garage next door was used to house even more memorabilia.

Tucked away behind all this, and shaded in tall elms, was the house in which Gary and his wife, Lena, lived. “My mom felt like this was just another adventure for my dad. She was a total sweetheart. Anything my dad wanted to do, mom went along with it. She would let him sleep late, walk down at 5 or 6 in the morning, get the coffee started, and go down to open the gate. It was a complete love story.”

The Younger Years

Gary G. Turner was born on February 3, 1944, to Henry and Dorothy Turner, and grew up in Abesville, Missouri, a rural community south of Springfield. He was the first of two boys and two girls. Gary and his family were “fruit tramps” both locally and far afield, as explained by third-born child Steve Turner. “They would pick fruit, he and his mother and father. As a youngster, his parents took him and his siblings from Missouri to southern California to pick.”

This went on for several years, from 1952 to 1956, when the last child (Beverly) was born. Gary’s sister Leah Faucett recalls those early trips west: “I was just a little kid. The two boys got the back seat of the car, and I got the floorboard. We spent a lot of time in the car,” she chuckled. They picked cherries, strawberries, almonds, and whatever was in season, working their way as far north as Oregon, before returning to winter in the Springfield area. “We just followed the harvest. We were worse than poor.”

Roamin’ Rich Dinkela was especially close to Gary, in spite of a 35-year age difference. He recalled how Gary would often regale him with the same family stories of loading up the beat-up car and heading west, the kids tumbling around in back. It was a Grapes of Wrath style tale, even if more than a decade after the movie and book. California was the Promised Land, even if only for a few years, but it set the stage for a future chapter in Gary’s life.

“He wound up back in Missouri, where he met mom (Lena), and had four children,” Steve continued.

Lena was born on December 4, 1942, and grew up in the Hurley and Galena communities of southern Missouri, not far from Gary, but unbeknown to him until years later. They met when Gary worked for Lena’s parents at their gas station in Springfield, where both families had moved.

Gary lived just off of 66, and walked across town to get to work, saving his paychecks to buy his first car, a ’53 Ford.

The couple married in 1959 in Springfield. “They then moved back to California and he became a gunslinger at Knott’s Berry Farm,” Steve said, uprooting the first two of their children for the cross-country trek in the late-1960s. It was a trip west, little different from the one he had taken with his family as a child, once again in search of work.

Knott’s Berry Farm, which today is known for its thrill rides, was then focused primarily on serving up more or less authentic re-creations of the Old West, including gun fights and train rides, in which park visitors were treated to an action-packed robbery. It was here that Gary Turner unwittingly cut his teeth as an entertainer, learning how to interact with the general public, albeit according to a rather rigid and predictable script.

Wallis recalls one conversation with a hearty laugh: “’You know, Michael… you’re talking to a man who has robbed his share of banks.’ He was as much a real bank robber as I am a real Sheriff.” Wallis of course was playing up on his role in the successful Cars franchise of the stern, but loveable Sheriff.

Asked where he got his sense of humor, Gary humbly replied, “Oh, I don’t know. I don’t think I have a sense of humor. I guess I just love what I do. If you love what you do, you can laugh about it.”

“He had that spark of being an entertainer, and he used it well. You always know when you have the audience right in the palm of your hand, and there is absolutely no better feeling in the world than that. I think that Gary got a lot of pleasure out of what he did, and the key is [that] he cared about people,” Wallis remembered.

Barb confirmed her father’s wit and humor: “I checked my birth certificate. I sent off to California to get it and I laughed when I received it and it said that my dad was an entertainer. I asked my brother Steve and his said that his father was a train bandit. He was always entertaining someone. How many kids can say that their dad was a train bandit?”

“Then he had a used car business in ‘77 or ‘78 that was very, very successful. Anything that he touched, he made it come out like the station is today. It was on the corner of Beach Blvd and Ball Road. It was called Beach Ball Car Company,” Steve recalled.

“Now, just so you know me, and understand me a little bit better, you’ve heard about hillbillies? Well, me and my wife come from the hills. We’ve been married since we was 16-years-old. Fifty-one years, and we weren’t even related. Now, her kin folks are all related. She gets mad when I say that,” Gary shared without a hitch back in 2012. Ba da bing. Humor a la mode.

Around 1979, Gary and Lena packed up the kids and moved back to the Missouri Ozarks, settling in the Paris Springs area. They wound up acquiring the small homestead from family members who parceled it out from its immense acreage. Thus was born the location for the new Gay Parita station, now visited year-round by 66 travelers.

“My aunt and uncle owned this property. They bought it and it had 80 acres. They separated it off and asked my mom and dad if they wanted to buy some of it, the house and a few acres. He bought it in 2003, and he worked out of his garage,” Barb explained.

Getting Started. Again.

Back in the Midwest now, Gary drove a truck for 23 years. Upon retirement, his relatives set to building the replica station for him, unknowingly at the time setting in motion what would quickly become one of the premier highlights along Route 66. In fact, Gary Turner became one of only a handful of human roadside attractions up and down the route, far more endeared among roadies than the buildings that they inhabit. People may have stopped at the building, and indeed photographed it with reckless abandon, but they came there to see Gary first and foremost.

“He said that he was going to make this place the most famous place in the world. He called every newspaper that would talk to him, all over the United States. They would come there and spend the day with him,” Faucett recalled.

“You know, I meet some of the nicest people you’ve ever met in your whole life from every country in the whole world. There’s not one country, I believe, that has never been here. The truth of the matter is, they are wonderful people. They’re just like your neighbor,” Gary waxed poetic.

Gary would sometimes stay in his “office” (how the tiny station was known colloquially) until midnight, lingering with late visitors who hopefully had planned ahead for lodging down the road. After locking the gate, he would tip- toe into bed beside Lena.

He loved to regale visitors with stories, and guide people to other attractions and good food farther down the road, often using David Wickline’s two pictorial books as his Bible. “This is The Big Texan. They have a steak that’s about this big and this tall. And if you can eat this, and everything with it, it’s free. If you can do it. You’ll come out looking like a Louisiana tick, that’s what you’ll look like,” Gary deadpanned.

“Now, when you guys get to Williams, Arizona, take the train ride if you’ve got time. It’s about a 4-hour ride, and everyone says it’s really, really good. And this here is one of my favorite places. This is Oatman, Arizona. These donkeys live here, they walk through the streets. They’re probably the descendants of the donkeys that worked in the mines. They’re gonna love you… until you run out of carrots, and then they’re gonna find somebody else to love.”

It was difficult for visitors to resist such armchair tour- guiding. “He just loved talking to people. He was a natural BSer.” Faucett laughed.

Most importantly, though, was Gary Turner’s admonition to everyone: “You’re off to the adventure of your life.”

The impact he had on tourists was profound, perhaps none more than with Dinkela. “Gary was just so eager and excited to please people and make them his friend. If you ever met Gary, you probably got one of his signature shirts. He had that little heart that he used to draw… (Heart) Kicks on 66, Friends for Life… Gary. He was so eager to be everybody’s friend and make sure that they had the best possible experience that they could get on 66. He wanted them to have the trip of a lifetime. He really changed my experience on 66. Gary opened up my world. I was a pathfinder, but Gary pointed me toward the people of 66. There’s a balance in everything. That was the lesson that Gary taught me. ‘Rich, you’re doing it all wrong. It’s not about the path. The path wouldn’t be anything without the people,’” Rich recalled wistfully.

Gary’s generosity in love, friendship, and food at Gay Parita, though, were owed in large part to his formative years as a picker, with his family trying to survive poverty. “I remember Gary as a generous person,” Beverly Enloe, his sister, said. “He once took coffee and donuts down to the Mueller Company for four days straight while workers were on strike. He was very pro-union. And I remember my mom telling me of when he had the used car lot in California, he gave a car to a couple who had broken down. He just gave it to them,” she added. “He was a very kind-hearted person.”

“Because of his lifestyle when he was younger, that explains his lifestyle when he was older. If you don’t know any better, you don’t know you’re poor,” Faucett related. Once he figured it out, though, it framed his outlook on life.

Death Became Them

The days and months leading up to 2015 were not good ones for Gary and Lena, as health issues began to take their toll. Both had been as inseparable as pie from ice- cream all their years together, Lena supporting Gary selflessly. Gary had multiple health issues problems, while Lena suffered a stroke.

“His health started to show decline in the early- to mid-90s. It just got progressively worse. He had emphysema, and he had two heart attacks that I remember. He had a stroke also,” Steve recollected. A lifelong smoker, Gary struggled to relinquish the habit. “He would say he was going to quit, and the next day, it didn’t happen.”

Gary seemed to bounce back in January of 2015, offering a ray of hope that he might be with us a while longer, but his condition took a turn for the worse in the last week of the month. On January 22, he had one brief moment of his former self, and begged Barb, from his hospital bed, for a slice of German chocolate cake and milk. Barb got the go-ahead from the head nurse, ran to the store, and brought back her father’s last wish.

But it sat unconsumed on the bedside tray, as he slipped away before he could enjoy them.

As can be expected, Lena took Gary’s death terribly, and found it difficult to live in his absence, passing on herself on May 18, barely four months after Gary. “She died in her sleep. She had diabetes and cirrhosis of the liver. I remember after dad passed her saying, ‘He wasn’t supposed to leave me alone.’”

“I was with him during the last hours of Gary’s life. I got to say goodbye to him. I don’t know what I would have been like had I not been able to say goodbye. That was a rough moment for me. He was so selfless. All he cared about was people coming here and seeing America, not taking anything for granted. He cared about people. He was considerate, he was kind. Even if he didn’t like you, he was kind to you,” Rich lamented.

Barb spent a few weeks in Missouri tying up loose ends after Gary died, and tending to her mother. Still employed back in South Carolina, she wound up commuting back and forth to Missouri, first in March to Gary’s memorial service, and then in May when Lena passed away on the 18th. That the couple should go in such short order together is testament to how close they were throughout their married years.

Meanwhile, the future of Gary’s Gay Parita was very uncertain.

Gay Parita, Part 2

The Gay Parita station sat in quiet repose for months following Lena’s death. No doubt the ghosts of Gary and Lena mourned the inactivity, but so did legions of Route 66 travelers for whom this was a frequent and necessary stop shortly after leaving the busy streets of Springfield, Missouri.

The grass and weeds grew. The flowers failed to bloom. Worse yet, vandals started claiming some of the many antique signs and artifacts that made Gay Parita one of the most popular and unique roadside attractions on 66.

Barb describes what happened during this period: “The station sat empty…. almost a year. My mom passed away at the end of May 2015. We packed up a lot of stuff after mom’s death, but thought, ‘Let’s just leave the signs so that the tour groups can see them.’ When they started getting stolen, my aunt and uncle came and took down the rest. One tour operator told me, ‘If we have to drive by there one more time and see all the signs gone, we’d rather just see it burned down.’”

That revelation is what finally jolted the family to action. Among the four Turner siblings (two sons and two daughters, three of whom live within an hour), it was Barb and husband George who were in the best situation to completely up-end their lives and assume the roles Gary and Lena once held.

“We got here on April 1, 2016.” Barb abruptly left a career in theater management in Charleston, South Carolina, and began packing. Without any children to raise or other commitments, the couple was more portable than the other siblings, and set to downsizing their possessions for the 1000-mile move west… a move similar to the one Gary and Lena had taken 55 years earlier when they pulled up stakes and headed to California.

“It just takes time to do all this stuff,” Barb sighed. “I quit my job of 23 years. After we got here we threw everything into the house and started bringing out all the stuff we had packed away. We live in the house now. I thought it would be scary at first, but it is so comforting to me.”

Sorting through the belongings of a couple married for 56 years was no small task, even if their home was only 988 square feet with a basement. Add in Gary’s ephemera, knickknacks collected through the years and gifts from hundreds of visitors, and it began to look like an episode of a popular cable TV show.

Barb recalls finding her father’s long-silenced flip phone. “It totally reminded me of Rainman. I looked at his phone and there were no names… only numbers. He remembered everyone by number. My whole thing about coming here was seeing that it was preserved. I didn’t want to see it being auctioned off. It was about making sure that I was here. I promised dad that I would take care of mom and the station. I had to sell my house and quit my job. Dad got me home no matter what.”

Gary Turner’s impact on Route 66 has been noted by many, particularly the people and communities nearby Gay Parita in Missouri. He has been sorely missed.

“We miss him dearly,” said Bob Gehl of the Missouri Route 66 Association. “Barbara has done such a great job in welcoming the traveling public to Gary’s station and his site. He made everyone feel like they were the most important guest he had ever met. Gary was one of the consummate hosts of Route 66. If we could have cloned him and had a thousand more, we would have done it. He was that much of a supporter.”

“It takes a storyteller to know a storyteller. We clocked many hours just swapping stories. It was like a tennis match. We told true stories, and we told yarns. We both believed in the old adage, ‘With each telling of the story, the story should get better’,” Wallis reminisced.

“It’s so bittersweet being here. It’s hard for me to talk about them. I don’t think the process of healing ever ends. I live it every day,” Barb continued. “But in the end, this is my life.”

Today, Gay Parita has been given a new lease on life. The grounds are immaculate. Replacement signs and artifacts have been found or borrowed, like a 1930 milk truck. Landscaping is neat and tidy, with a memorial garden behind the station, a vegetable garden, and a large pen where a pig, two geese, and four ducks call home. The couple plan to add permanent restrooms, and even a small theater.

It is a grueling 24/7 job for Barb and George, particularly from March through to the end of October. For eight months a year they are on call, but still welcome the occasional winter guest as well. “A lot of times we don’t go inside until 10pm. Sometimes, we have people here until midnight. This is a once- in-a-lifetime thing for most people. You have to expect things like this. If you’re not open and they can’t see it, you’re going to lose it. They just can’t come back tomorrow. We try to make sure we catch everyone.”

“The beauty of our people who are scattered and littering the shoulders of Route 66 is that they can stay right where they are, and the world comes to them. Gary never had to leave, the world would come to him and Lena,” Wallis acknowledged. The same is true today for Barb and George.

The station is a constant reminder to Barb of how influential her father was, and what he did for Route 66. She feels his presence daily, as do the thousands of people who pass through that gate. Gay Parita looks much the same as it always did, perhaps a little neater and tidier in places where Barb has left her fingerprints, but the vibe is no different.

There is no such thing as a 15-minute visit to Gay Parita, with or without Gary. Watermelon and sodas are still offered free of charge in the pavilion. It’s a place where there are no strangers, and conversation is served in abundance. You forget the heat, the humidity, the flies, because this is the day’s premier event, and this is not the typical Missouri front porch.

Wallis laughed aloud, “If you’re in a hurry and you stop at Gay Parita, you’re in trouble! That’s the way it should be. If you’re a true open road traveler, then Gary Turner and Gay Parita were made for you. You shouldn’t be in a hurry when traveling the Mother Road.

“Although he might not have settled in to the road until 2005, in a way, he was always on the road, if not physically, then certainly in his head and heart. He was always a road warrior, whether he was entertaining people in California, driving a truck, or picking apples,” Michael Wallis continued. “He was a guy of basics. Love your neighbor. Be good to people. If you can tell them a good story, you better do it, and send them off knowing a little more about themselves.”

And that he did. But only after a bowl of ice cream and watermelon.