Behind almost every great success story lies an inspiring tale of struggle, ambition and ingenuity — and in the case of the Burma-Shave Company, it also included an ingenious advertising and marketing concept that defined the Burma-Shave cream as one of the most popular brushless shaving creams in the United States.

The 1920s was a decade of rapid change. Men and women were suddenly clumped together in raucous and loose social gatherings. Prohibition ironically ignited an insatiable demand for alcohol, and innovations in all aspects of life were on the rise. Seeking relief from the horrors of the Great War, people began searching for ways to make their lives easier and more enjoyable. This newfound desire for innovation targeted the daily routines of many Americans — including the way that men groomed.

As far back as 100,000 years ago, based on cave painting depictions, it is believed that men would pull out their facial hair using seashells as rudimentary tweezers. This approach slowly advanced, and men began using makeshift razors from flakes of obsidian or shells. The Romans were known to apply pumice stones and oils to their skin after a shave, while treating any nicks with ointment. But it was the Egyptians, forced to shave under the orders of Alexander the Great, who put into practice the use of oils as shaving cream. And hence, the traditional art of wet shaving - the use of shaving creams, brushes, and initial wrapping of the face, was born.

In mid-19th Century England, a brushless shaving cream called Lloyd’s Euxesis emerged, irreversibly changing the way that men shaved. The cream did not create lather and eliminated the need for a brush or shave mug, requiring less time than a traditional shaving cream. For men looking for convenience and speed, the brushless shaving cream was the answer. However, the brand proved to be a major misfire. Consumer reports claimed that the cream would mildew easily and adopt an unsavory green color, making Lloyd’s Euxesis a less-than-favorable option. Little did the English brand know that a more successful brushless shaving cream would soon spring up on the frosty soil of Midwestern America.

Burma-Shave, a witty, homegrown brand hailing from the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota, uprooted Lloyd’s Euxesis failed attempts at reinvention and conquered the task with determination, intelligence and, most of all, an abundance of heartfelt humor. But before Burma-Shave earned its place as one of America’s most popular shaving creams, it lived in the dreams of an inventive, determined businessman named Clinton M. Odell.

First Come Struggles, Then Massive Success

When Robert Odell began experimenting with chemicals during his leisure time, his son, Clinton M. Odell, should have sensed that significant changes were on the horizon. After all, it was the late 19th Century, and invention was on the rise. Steam engine trains were now roaring across the nation’s landscape, connecting people in ways that once seemed unimaginable.

Like many young men during the era, Robert was raised on the idea that self-reliance and hard work made a man. According to Robert’s great-grandson, Clinton B. Odell, it was his great-grandfather’s ingenuity and grit that set his family on a sure path to success and inspired his grandfather, Clinton M., to make his own entrepreneurial dreams a reality.

“[Clinton M.] was terrific,” Odell said. “He really was a self-made man. Actually, his father, Robert Ransom Odell, immigrated from New York state in about 1880... and I think a lot of my grandfather’s push and drive was from his father, because in those days, they would think nothing of having their sixteen or seventeen-year-old sons ... just telling them to get out of the place, and with this young man, that’s exactly what he did. He spent about half a year in California, and in the year 1892 or 1893, that’s when my great-grandfather [Robert] got the energy and drive he ended up having, because he was a true entrepreneur.”

“[Robert] went through law school at the University of Minnesota, and consequently, he started a law business, but he got a little tired of that. After that, he went to one of the first insurance businesses in Minneapolis, formed that with a good friend of his, and it simply got to a point where that wore him out. So, he spent about four years to recover — he had a nerve disorder called sciatic rheumatism, and it evidently was quite sensational, and it almost wiped him out. But then he came back, and he had to quit the insurance business. That company was called the White and Odell Insurance Company. So, he came back, and he was looking for something to do. He had a family to feed and what have you.”

According to Clinton B., concocting the perfect formula for Burma-Shave was a matter of trial and error: “My grandfather [Clinton M.] worked on a cream with his father, Robert — he liked to dabble in chemicals and what have you, although he was a lawyer and an Indian agent from this particular area. My grandfather ended up setting up a written agreement with his dad where he could market the product, which my great-grandfather had messed around with. At the time they called it Burma-Vita. Burma-Vita consisted of oils, actually, from a ship captain my great- grandfather got to know very well. They manufactured it, and they called it a liniment. My uncle always told me that my great-grandfather was up in an office in the old Globe Building in downtown Minneapolis. He said that he could always tell when his grandfather was messing with those chemicals because he could smell them. In those days, there were a lot of openings for successful products, or improved products, in so many different areas. So, they tried to market Burma-Vita ... It just didn’t work. They couldn’t get it to sell.”

In Frank Rowsome, Jr.’s book, Verse by the Side of the Road: The Story of the Burma-Shave Signs, Clinton M.’s son, Leonard Odell, spoke to Rowsome about the evolution of Burma-Shave from an unprofitable liniment to a highly successful brushless shaving cream.

“Well, we sure starved to death on that product [the liniment] for a couple of years. With a liniment you have to catch a customer who isn’t feeling well, and even when you do, you only sell him once in a while. The wholesale drug company in town, the people that we got the ingredients from, kept reminding dad that it would be better if we could find something that we could sell [to] everybody, all the time, instead of just hunting for people who were sick. They gave dad some Lloyd’s Euxesis to see what he thought of it.”

In 1925, when liniment sales were at an all-time low, a local chemist named Carl Noren walked into Clinton M.’s office to ask for a job. Some time prior to this fateful meeting, the same man had been hospitalized for a serious illness but had made a full recovery. Moved by the man’s story, Clinton M. wrote Noren a Christmas card with twenty-five dollars tucked inside. Evidently, Noren felt that he should perform an act of kindness in return.

When Clinton M. asked Noren if he could try his hand at a brushless shaving cream, the chemist immediately started experimenting on a formula. After 143 attempts, he achieved the final brushless shaving cream formula, and thus, Burma- Shave was born. Around the time that the Burma-Shave Company emerged in 1925, Clinton M. married Grace Evans Odell, with whom he would have Leonard and Clinton B.’s father, Allan, and later George in 1942.

Leonard (left) and Allan (right).

Within the business realm, Burma- Shave experienced setbacks like any other fledgling company. For one thing, the company’s location was an impediment in itself. “In Minnesota, you always have problems in the winter,” Clinton B. said. “It’s freezing. And, I can recall a time when they shipped a whole box car load of Burma-Shave, and when it got down to Chicago, it had frozen. So, they had to bring it all back, destroy it, and start over again.” At the same time, other brushless shaving cream brands emerged, including Gillette and Barbasol, threatening the stability of the small business. Nevertheless, the humble family-run brand managed to stay afloat due to a clever advertising strategy.

It’s All in the Ads

With the creation of Burma-Shave, the Odells found themselves in the throes of a daunting, new commercial venture. Compared to other shaving products of the time, the Burma-Shave cream was not particularly different or unique. Sales were markedly slow to begin with, and the company was in need of a marketing hook that would effectively showcase their new product and brand. That is, until Clinton M.’s son, Allan, came up with an inventive, amusing advertising concept, which would prove to be tantamount to the company’s success.

This was the same decade that saw the rise of Henry Ford, who had released his Model T, which sold in the millions, and automobile culture had taken off. Having recognized the success of other roadside signage during his travels through Illinois, Allan saw an opportunity to promote the new shaving cream using road signs with cheeky, quirky and memorable jingles — a humorous take on an advertising classic. So, he asked his father to give him money to start working on his sign ideas. When Clinton M. asked his friends what they thought of Allan’s idea, they all agreed that it would never work. Nevertheless, Allan persisted, and his father finally relented and gave him $200 to purchase used sign boards. Allan and his younger brother, Leonard, created the first set of Burma-Shave rhymes and installed them on Route 65 to Albert Lea, Minnesota, as well as on the road to the neighboring town of Red Wing.

In his interview with Rowsome, Leonard discussed how the company’s early signs prompted a greater demand for Burma-Shave, despite his father’s uncertainty. “By the start of the year [1925], we were getting the first repeat orders we’d ever had in the history of the company — all from druggists serving people who traveled those roads. As he watched those repeat orders rolling in, Dad began to feel that maybe the boys were thinking all right, after all. He called us in and said ‘Allan, I believe you’ve got a real great idea. It’s tremendous. The only trouble is, we’re broke.’”

Despite his hesitancy, Clinton M. decided to give his son’s concept a chance. Backed by an ailing company and an advertising notion that was seen as a failure, Clinton M. bravely employed his superior sales knowledge to sell 49 percent of the stock in less than three weeks.

In 1926, the company acquired its first store — a nondescript, white clapboard house on E. Lake Street in Minneapolis. Here, they began manufacturing their brushless shaving cream and famous signs.

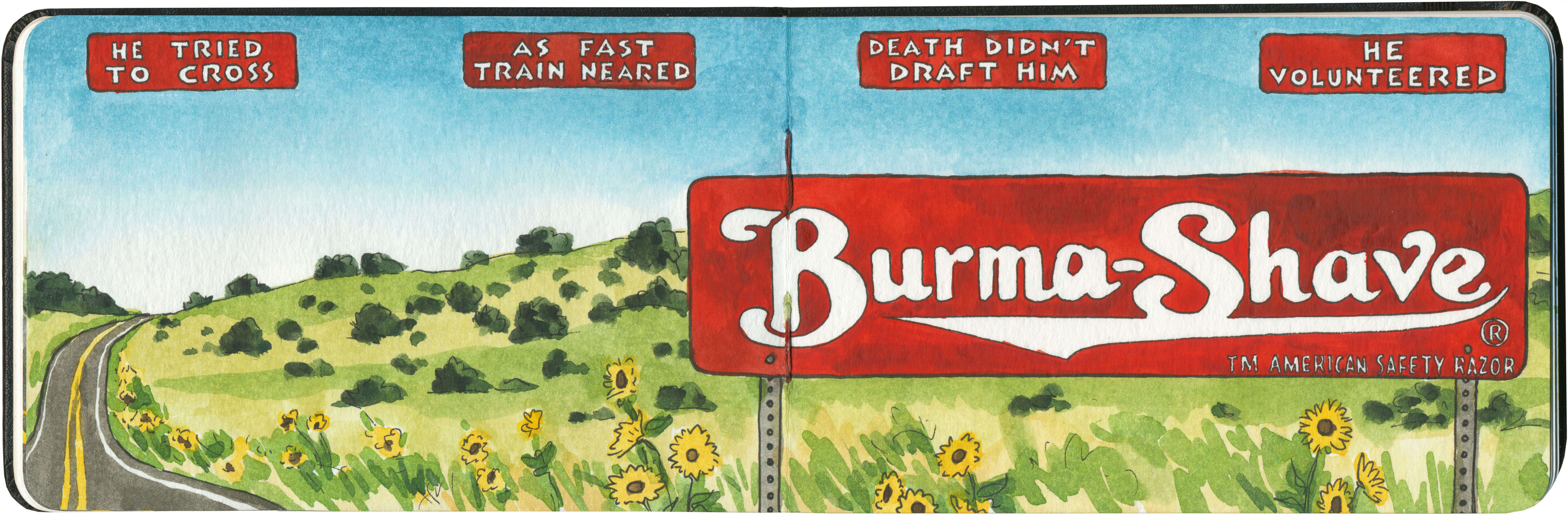

Every aspect of the Burma-Shave Company was a product of precise experimentation and calculation — even in terms of the ways in which the signs were placed along highways. The signs were arranged in sets of six, placed 100 feet apart, making it so that travelers had exactly three seconds to read each sign driving at a rate of 35 mph. The signs consistently rhymed and created interest in travelers to know what the punch line would be. They were composed of red painted boarding and white letters — a combination of colors that made the signs stand out from other roadside signage. At the peak of Burma-Shave’s successful run, there were over 7,000 signs erected along American highways in 45 states.

alongside Allan Odell. December 8, 1958.

According to Rowsome, a Burma-Shave signage scout, who they called the “advance man,” would travel America’s highways in search of ideal locations for signs. Often, such locations were found on farmland, where there were fewer large billboards and greater long-distance visibility. Farmers often enjoyed Burma-Shave signs that were planted on their land and wished to establish long-lasting relationships with the humble, family-run company.

In Rowsome’s words, “Mostly the relationship between farmers and Burma-Shave was an amiable one, with many leases extending over decades. ‘Oh, occasionally we’d get a man who’d pull down some signs to patch up his barn,’ noted John Kamerer, head of the company sign shop, ‘but it was mainly all the other way. The farmers were kind of proud of those signs. They’d often write us if a sign had become damaged, asking us to ship a replacement that they’d put up themselves. In the years when we brought old signs back here to the plant, when lumber was short, I’d sometimes see where they had repaired or repainted signs on their own hook, often doing a fine job of it, too.’”

Just as Allan predicted, the signs proved to be a hit with road travelers, providing people with a bit of roadside entertainment in an age where conversation and scenery stood in place of handheld technology. “They were enjoyed,” Clinton B. said. “They were pleasant. A lot of this took place during the Recession. Back in 1929, ’30, ’31, things were tougher in this country, and people enjoyed them because they were happy. They weren’t anything that was discouraging or upsetting.”

Burma-Shave rhymes proved to be so popular, in fact, that the Odell family decided to hold yearly contests for people to submit their best jingle ideas, which people evidently loved as much as the signs themselves. “They were, of course, very popular — the sign contests,” Clinton B. said. “They had two a year. And I always knew when they had a contest going because my dad ... He always got off-color ones, as you can imagine, and some were very funny. So, my dad would tell his secretary to compile the off-color ones and bring them home. And my mother and he would go into our library and close the door, and I’d hear all this uproarious laughter.”

In addition to promoting their product, Burma-Shave jingles covered a variety of topics and even approached difficult subjects, such as drunk driving. According to Clinton B., it was important to his grandfather that Burma- Shave signs avoid controversy, and he was very meticulous about which jingles would make it to the road. While there were many memorable Burma-Shave jingles, Clinton B. had his own favorite: “Does your husband — Misbehave — Grunt and grumble — Rant and rave? — Shoot the brute some — Burma-Shave.” As for Clinton M., Allan and Leonard, they seem to have shared a favorite: “Within this vale — Of toil — And sin — Your head grows bald — But not your chin – Use — Burma-Shave.”

While Burma-Shave signs were most commonly seen along American roadways, they could also be found in other places outside of the country. During the 1960s, the U.S. Army had the idea to plant Burma-Shave signs in Korea and Burma for servicemen to get a glimpse of a heartwarming reminder of home. The signs even made their way into the frigid continent of Antarctica, where servicemen were stationed during a series of missions code named Operation Deep Freeze. In truth, Burma-Shave signs had become a symbol of America, and for this reason, they had the very special ability to comfort those who were thousands of miles away.

The Burma-Shave Legacy Lives On

For decades, the Burma-Shave Company dominated the shaving cream industry, providing quality products backed by a humorous, loving family. The company met its end when it was sold to Phillip Morris of the American Safety Razor Corporation on February 7, 1963. As a result, Burma-Shave’s famous signs were removed from American roadways, taking decades of cherished memories with them. Today, only one full set of Burma-Shave signs exists, and it’s housed in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. It also happened to be the favorite jingle of Clinton M., Allan and Leonard.

In 1958, Burma-Shave’s co-founder, Clinton M. Odell, died, leaving the family business to his sons. Decades later, in 1991, Leonard died, followed by Allan in 1994, Grace in 1999 and George in 2011. Today, the Burma-Shave legacy lives on in Clinton B. Odell, who shares his family’s story with a pride and happiness that transcends the passage of time. “It was an easy-going, fun family, and they laughed easily. These three men were wonderful men, and I really miss them.”

Although times have changed drastically since Burma-Shave sat fully stocked on store shelves, the company’s influence on men’s grooming and advertising remains unprecedented. What began as a single liniment gave way to a wide array of products, including brushless and aerosol shaving cream, aftershave, talc, tooth powder and razor blades.

Considering Burma-Shave signs defined road travel during the mid-20th Century, there’s no question that the signs have made a profound impact on American popular culture. They were often featured in hit TV shows during the 1970s and even served as the inspiration for songs by legendary artists, such as in Roger Miller’s 1965 tune “Burma-Shave.” But Burma-Shave’s presence in popular culture is still very much alive and well today, finding its way into the 21st Century in ways many people may not realize.

For the hit 2006 animated film, Cars, Route 66 served as the movie’s main inspiration, but Burma-Shave also made a subtle guest appearance. According to Michael Wallis, author ofRoute 66: The Mother Road, his time as a consultant for Cars allowed him to implement Burma-Shave signs into the film.

“I actually often took the whole creative team out on the road. I was able to take them to places and introduce them to people they would never have met, and all of those places made it into the film. Every car or automobile comes from real life ... Mater, for instance — he comes from about four or five different bizarre characters out on Route 66. I made sure there were ample doses in the film of some of the iconic sights of Route 66, and that included Burma-Shave signs. There are Burma-Shave signs in Cars Land in Disney, the park that Disney created, and I was their consultant as well to create this 12-acre park that is Radiator Springs come-to-life. It’s very cool. There are Burma-Shave signs along a stretch of road. They aren’t Burma-Shave, though. What they’re pushing is the product that sponsored Lightning McQueen as a race car driver — his official sponsor, which is called Rust-eze.”

Truly, Burma-Shave became an emblem of road travel, during which time the journey along the road was often as exciting as the destination. Naturally, the Mother Road was home to many Burma-Shave signs, and one town in particular is doing its part to preserve this aspect of its history. In the small town of Seligman, Arizona, in 2007, Carol Springer, District Supervisor of the Yavapai County Public Works, decided to erect a set of Burma-Shave signs along Route 66 to commemorate the town’s history. After gaining permission to use original Burma-Shave rhymes, they successfully recreated sixteen signs, which are planted along the highway that runs through Seligman and still stand today.

In addition to Seligman, the town of Towanda, Illinois, takes great measures to honor its Route 66 heritage, boasting a collection of Burma-Shave signs. At the Towanda Route 66 Parkway, visitors can learn about the vibrant history of the Mother Road by walking along the parkway’s beautiful trail, which features old Burma-Shave signs that used to sit along this old portion of the route. The parkway’s other signs showcase stories and photos illustrating other Route 66 landmarks in Towanda’s history.

Burma-Shave signs, among other pieces of vintage Americana, represent a unique aspect of our nation’s cultural heritage, beckoning to those with an appreciation of America’s past — and present. While the influence of Burma-Shave on popular culture is profound, so is its place in the hearts of those with a love of roadside history, who hail from places around the globe. The hunger for vintage Americana is one that will never be satisfied as long as a love for road travel continues to thrive.

While the Burma-Shave Company is more commonly defined by its beloved jingles, the entrepreneurial genius of the family behind it deserves its own form of recognition. In truth, the Burma-Shave Company defines the American Dream. Out of his own creativity and profound business instincts, Burma-Shave’s founder was able to conjure up his own legacy. He did so in an era unfacilitated by the Internet, drawing on his family’s hard work and enthusiasm to fuel his dream. In retrospect, it’s safe to say this dream became a flourishing reality, thanks to one recreational chemist and his advertising-savvy grandson.