Laura Ingalls Wilder once wrote: “I am beginning to learn that it is the sweet, simple things of life which are the real ones after all.”

For Wilder, life in a pioneer family in the late 19th Century was, truthfully, seldom simple or sweet. Born during the Reconstruction era, Wilder was thrown into a world recovering from a terrible war, with the added unpredictability of traversing untamed, often dangerous wilderness in a cramped, covered wagon.

For young readers, Wilder’s tales of harsh South Dakota winters, exploring the wild with Jack the bulldog, and the soothing, airy sound of Pa’s fiddle kindled their tender imaginations. Since the first book of the Little House series, Little House in the Big Woods, was published in 1932, Wilder’s books have made a profound impression on the minds of countless children who have found solace in the simplicity and authenticity of Wilder’s life story, as it is told through the innocent, yet keen perspective of her much younger self. Michelle McClellan, Professor of History at the University of Michigan, was one of the millions of people who fell in love with the Little House series as a child.

“I got the yellow boxed set as a Christmas gift from my parents when I was in elementary school,” McClellan said. “I loved them immediately, I think for a few main reasons. Laura is such a lively, multifaceted heroine, so that attracted me quite a bit. I also already liked history yet had not encountered many stories about girls or families in the past, so the Little House books drew me in for that reason.”

Through her semi-autobiographical book series, Wilder reveals the truth about life on the frontier, sharing harrowing stories about catastrophic blizzards and a grasshopper plague that destroyed their wheat crop. And yet, optimism and humor pulsate throughout Wilder’s series, revealing the author’s uniquely beautiful perspective on life. In the sixth book of the Little House series, The Long Winter, Wilder writes: “Laura felt a warmth inside her. It was very small, but it was strong. It was steady, like a tiny light in the dark, and it burned very low, but no winds could make it flicker because it would not give up.” For Wilder, every terrible truth had a silver lining, which was found in the warm embrace of family and a glowing fireplace.

A Pioneer Girl’s Childhood

On February 7, 1867, Wilder was born to Charles and Caroline Ingalls in a log cabin outside of Pepin County, Wisconsin. She had three sisters, Carrie, Mary and Grace, and a younger brother, Charles, who died when he was just nine months old.

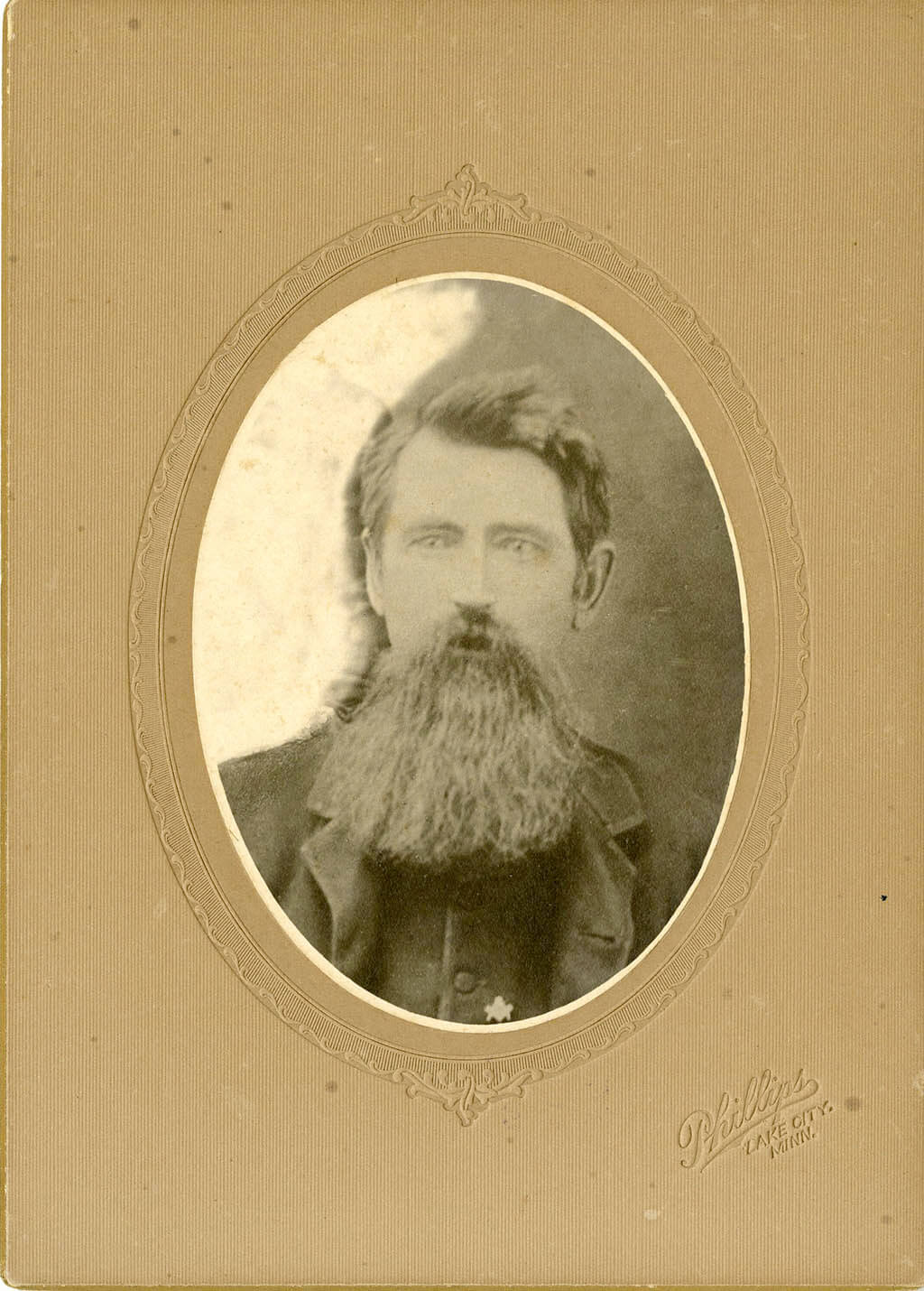

Charles Ingalls, referred to as “Pa” throughout Wilder’s books, set out to provide for his family by any means possible. It was this determination that led Charles to take his family across the Midwest in search of a better life and a stable career. In 1874, Wilder and her family left behind their log cabin in Wisconsin and traveled to southeastern Kansas, or “Indian Territory.” While household duties kept the entire family occupied day after day, their chores were interrupted by intermittent catastrophes. For instance, the following spring, the entire family fell ill with malaria.

But regardless of the daily hardships Wilder and her family faced, she maintained a keen interest in the ever-changing landscape in which she constantly found herself. Nancy Koupal, Director and Editor-in-Chief of the Pioneer Girl Project, said that Wilder’s love for the natural world characterizes all of her writings.

“She was at home in nature. She truly loved the natural environment in which she lived. She had true affection for wildlife and flora and foliage. So, that stands out to me because it’s palpable in all of her writing.”

Family Matters

For those who read the Little House series, one of the aspects of Wilder’s life that stands out the most is the tight-knit bond of her family, which enabled them to endure constant setbacks. In Koupal’s opinion, it’s this prototypical family image conveyed in Wilder’s books that captivates readers of all ages.

“I think it’s that universal family that everybody wishes they had grown up in. They’re very supportive of each other. They make this unit against the world almost, and I think she captured something that almost every child wishes they had, and almost every adult.”

Wilder maintained a strong relationship with her parents until their deaths, which ultimately proved to be the motivation behind her Little House series.

“When she got the news that her father, Charles Ingalls, was on his death bed in 1902, she dropped everything and went to De Smet, for the first time in years, to be by his side,” said Caroline Fraser, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. “And although she didn’t travel to see her mother before she died, in 1924, I think that loss was nonetheless very [melancholic] and meaningful for her. It inspired her to write to her mother’s sister, Martha, to ask about their early lives. Those letters would become the catalyst for her long-cherished dream to write about her childhood.”

Her siblings lived the rest of their lives in South Dakota, where their pioneer adventures had ended. After attending a school for the blind, Mary moved back to De Smet to live with her parents. Following their mother’s death in 1924, Mary moved into Grace’s home in Manchester before making her final move to live with Carrie in Keystone. Unlike her TV persona, Mary never married Adam Kendall, a teacher at the blind school, nor did she teach. After having suffered a stroke and a battle with pneumonia, Mary died on October 20, 1928 at the age of 63.

Much like her literary sister, Carrie lived a notably exciting life. Carrie had always planned to be a teacher like Laura, but during her teenage years, she became a typesetter for the De Smet Leader. Eventually, Carrie managed various newspapers across the Badlands area of South Dakota for journalism mogul E.L Senn. In 1907, she traveled on her own to Topbar, South Dakota, next to the White River Badlands, and lived out of a tarpaper shack. Carrie settled down in Keystone in 1911 and continued to work in the newspaper business until she married David N. Swanzey the following year and became a stepmother to his two children, Mary and Harold, at the age of 42. Following in his stepmother’s adventurous footsteps, Harold later went on to help carve Mount Rushmore. Carrie died from complications with diabetes on June 2, 1946 at the age of 75.

After working as a schoolteacher in Manchester, Grace married Nathan William Dow in her parents’ De Smet home on October 16, 1901. Later in her life, she worked as a freelance journalist for several newspapers. She shared a similar fate with her sister, Carrie, and died from complications with diabetes on November 10, 1941 at the age of 64.

Almost all the Ingalls sisters were united by a shared penchant for writing, which impacted their lives in different ways. Every member of the Ingalls family, except for Laura, is buried in De Smet Cemetery, where they lay together under the vast, ever-changing South Dakotan sky, in the very place that witnessed the close of their extraordinary pioneer life.

Married Life

In the eighth book in the series, These Happy Golden Years, Wilder reminisces about the beginnings of her relationship with her husband, Almanzo Wilder, who was ten years her senior. While living in De Smet, South Dakota, at age fifteen, Wilder left home for the first time to be a teacher, which she did in order to pay for her sister, Mary, to attend a school for the blind. Since the schoolhouse where Wilder taught was twelve miles away from her family’s home, Almanzo would drive her back at the end of every school week. During these weekly rides, which sometimes consisted of risky drives through dangerous blizzards, the two fell in love.

The couple married in De Smet in 1885 and settled in a home Wilder built on land that he owned. The following year, the couple welcomed the birth of their daughter, Rose Wilder, who would later follow in her mother’s footsteps and become a writer herself under the name Rose Wilder Lane.

Like her childhood, the first few years of Wilder’s marriage were marked by profound misfortunes, which are chronicled in the final book of the series, The First Four Years. In 1889, the couple’s son died when he was two weeks old from “convulsions.” Later, after both Laura and Almanzo suffered a terrible bout of diphtheria, Almanzo was left partially paralyzed. Following this setback, the couple’s home tragically burned to the ground.

For the next few years, life was chaotic and unsettled for the young family. After spending a year living at Almanzo’s parents’ home in Spring Valley, Minnesota, they decided to try to start a new life in Westville, Florida, with the hope that the warmer weather would improve Almanzo’s health. Deterred by Florida’s unfamiliar, humid weather and feeling out of place among the locals, the Wilders moved back to De Smet in 1892.

While Laura and Almanzo’s marriage began with many obstacles, it never threatened to break the bond they formed and the love they had for each other.

“It was difficult, at times, because they weathered a lot of hardship and tragedy,” Fraser said. “But it was difficult in the ways in which many long marriages can be difficult. I do think they loved each other very much to the end: They argued and fought and made up again. Almanzo spoke about Laura’s temper almost with admiration, at times.”

The Move to Missouri

In 1894, the Wilders moved to Mansfield, Missouri, located about an hour’s drive from the beautiful city of Springfield, and purchased an undeveloped property outside of town with the money they had saved up. The home they built there, in which Laura and Almanzo would spend the rest of their lives, would eventually serve as the place where Wilder’s Little House series came to fruition.

“Rocky Ridge, the farmhouse that Wilder and her husband built on their land outside Mansfield, was the culmination of Wilder’s lifelong dream of having a rural home in a lovely, wild place,” Fraser said. “But while the farm was indeed in a glorious setting, life there involved virtually unending labor until the Wilders ‘retired’ late in the 1920s. I put that in quotes because retirement for them hardly involved putting their feet up and taking it easy. That’s when Wilder started writing her books.”

During the 1910s, both Laura and her daughter, Rose, embarked upon their writing careers. While Rose began writing for the San Francisco Bulletin, Laura began work as a columnist at the Missouri Ruralist. During her time at the Ruralist, Laura wrote columns, which advocated for the rights of farm women and shared her tips for the grueling farm work that characterized her days at Rocky Ridge Farm.

“When you read Wilder’s farm columns from the Missouri Ruralist, you see how her days unfolded — caring for chicks and hens, cleaning chicken coops, milking, hauling slops to pigs, separating cream, churning butter, gardening, canning, cleaning, ironing, washing dishes, baking, cooking,” Fraser said. “It’s incredible, the work these women did.”

For Rose Wilder, her writing talent sparked a taste for yellow journalism, which is interesting considering she would later work with her mother on the Little House series.

“I was particularly surprised by the revelation that Rose Wilder Lane began her career as a newspaper reporter in Hearst’s San Francisco, and became a kind of notorious yellow journalist – [journalism that presents little or no verified well-researched news] – inventing ‘autobiographies’ of Charlie Chaplin and writing bogus celebrity biographies,” Fraser said. “That’s an astonishing revelation, given that Wilder and Lane eventually end up collaborating, as writer and editor, on another fictionalized autobiography — the Little House books.”

While Rose developed her career on the West Coast, the Wilders settled into their new life in Missouri, continuing their farm work and getting to know their new neighbors. Laura, in particular, fully integrated herself into the local community.

“She became very involved in the community of Mansfield,” Koupal said.

“She joined clubs, she advocated for farm women, [and] she worked in various capacities in Mansfield at various times in her life. So yes, I would say she was very invested in that community.”

From the Prairies to a Publisher

Under her daughter’s persuasion, Wilder penned the first of her autobiographical works, Pioneer Girl, around 1930. Wilder’s autobiography remained unpublished until Koupal and others from the Pioneer Girl Project and the South Dakota Historical Society Press published an annotated version of it in 2014.

According to Koupal, Rose and Laura initially believed they would be able to publish the autobiography in magazine installments. When this proved unsuccessful, they determined Laura should compile her memories into children’s novels.

Despite the success of the Little House series, Laura and Rose’s relationship was undoubtedly strained. Fraser described unearthed letters exchanged between the mother and daughter as “fairly unguarded” and “pretty frank.” Ultimately, the discord between Laura and Rose that had been growing over the years resulted in estrangement.

“But the relationship between Laura and Rose was strained and was a disappointment to them both,” Fraser said. “In addition to the normal tensions of any mother-daughter relationship, they had the additional burden of their professional collaboration, which existed almost from the time they both became professional writers, in the 1910s. That tension grew particularly intense during the time they were working on the Little House books. On top of that, Lane lived with her parents for significant periods, and these were times when she experienced deep depressions and felt a lot of resentment toward her mother. Ultimately, they ended up living apart.”

Wilder’s Legacy and Its Impact

With an imagination as vibrant and colorful as her memories, Wilder was destined to create a cherished children’s book series. And yet, within the hope and love that permeates her books, there is a tinge of darkness that cannot be ignored.

Located about an hour’s drive from Route 66, the Wilder’s Mansfield farmhouse is open nine months out of the year. Visitors to Rocky Ridge Farm’s museum can view artifacts from Wilder’s life, including Pa’s fiddle, Laura’s handwritten manuscripts and Rose’s writing desk.

“A visit to the Mansfield home is just like a trip through the novels,” Koupal said.

“It’s something everybody should do who has any fondness for [Laura Ingalls] Wilder or her novels or just has any appreciation for that era of American literature.”

Recognizing the success of the Little House book series, Ed Friendly decided to create a television show based on Wilder’s novels during the 1970s. Friendly asked Michael Landon to direct the two-hour pilot movie, which aired on NBC on March 30, 1974. Landon agreed, under the promise that he be allowed to portray Charles Ingalls in the series.

When the entire TV series aired in September of 1974, the Wilder family’s pioneer travels entered the homes of millions of American households. Melissa Gilbert, who portrayed Laura Ingalls Wilder, became the face of the famous author, while Karen Grassle portrayed Caroline Ingalls, Melissa Sue Anderson played Mary and sisters Lindsay and Sidney Greenbush portrayed Carrie.

Unlike Wilder in real life and in the book series, Gilbert’s portrayal of Laura was exceptionally adventurous, traveling to the Pacific Ocean and getting trapped inside an abandoned cabin during a blizzard. Likewise, Grassle portrays Caroline as a meek wife and mother with an occasional fiery side, which wasn’t true for the actual Caroline or her literary persona. For his part as Charles, Landon remained fairly true to the real person and his literary equal, although he didn’t grow Charles’ beard. Interestingly, Dean Butler’s portrayal of Almanzo Wilder was more accurate in terms of the age difference compared to Wilder’s illustration in the novels, considering he was eight years older than his co-star, Melissa Gilbert. Regardless of the occasional disparities between the televised Ingalls family and their literary and real-life counterparts, the popular TV series made millions of viewers fall in love with Laura and her close-knit family.

Nevertheless, with fame often comes controversy. In 2018, the American Library Association (ALA) stripped the Laura Ingalls Wilder Children’s Literature award of the author’s namesake, due to the presence of derogatory depictions of Native Americans and African Americans in Wilder’s novels.

Regardless of the nature of these descriptions, the novels shouldn’t be deprived of their literary value. In McClellan’s opinion, the Little House books should be used to gain a better understanding of past prejudices.

“The books themselves are a historical artifact,” McClellan said. “They describe events that took place during the 1870s and 1880s, and they were written during the 1930s and 1940s. So, it’s not surprising that attitudes have changed a great deal. I’m not saying that we should excuse or ignore language and attitudes that are troubling to us today, but I don’t think that means that the books have no value. For one thing, Wilder expresses a diversity of views about American Indians and African Americans in her books, which helps us understand the range of attitudes in any one time period, as well as changes in attitudes over time. For another, I think the challenge for readers, teachers, historians and literary scholars is to use books like these to prompt important conversations about race and equality in the past and the present — not simply dismiss or ignore them.”

In an article published in the Washington Post, Fraser voiced her disagreement with the ALA’s decision, stating, “Whether we love Wilder or hate her, we should know her.” In her mind, the Little House books allow children to understand the harsh reality of American history. Regardless, Fraser said the ALA’s decision was one that should have been expected.

“I understand the ALA’s decision,” Fraser said. “It was a long time coming, and children’s librarians had been talking about the issue for decades. So, it wasn’t a snap decision, made at the spur of the moment. Children’s librarians voted on it and ultimately felt that their award needed to reflect a wider audience and a more inclusive sensibility.”

Whether readers love or hate Wilder’s books, the author’s influence on American literature cannot be undermined.

Undoubtedly, the Little House series defined the frontier experience for readers. Yet, Fraser argues, the romanticized depiction of pioneer life illustrated in the books and in the TV show evade the complications and difficulties of early settlement.

“Since Wilder completed her series in 1943, the Little House books have had a tremendous influence on how generations of schoolchildren viewed homesteading, farming, and American settlement ... By the time the television show came along in the 1970s, a whole new generation was primed to receive what became a very sentimentalized and nostalgic view of the Little House: the idea that homesteading and American settlement were a rousing success and reflected American values of independence and self-reliance. But as I argue in Prairie Fires, if you look at the ways that the books, and especially the TV show, fictionalize the Ingalls’ experience, you begin to realize that settlement and homesteading were a far more complicated affair, one that cost everyone involved, from the settlers to the Indians they displaced, dearly.”

The End of a Pioneer Era

Wilder truly lived a complicated, ever-changing life. From her younger years, traversing the undulating prairie lands inside a covered wagon, to her later years as a wife, mother and novelist, Wilder defined the image of the pioneer woman. She embraced change with alacrity, endured the darkest of tragedies and sought happiness through it all. And unlike many authors, she chose to share her story through the eyes of her childhood self, so that children could learn about the landscape, people and places that characterized the American frontier.

After suffering two heart attacks, Almanzo died on October 23, 1949 at the age of 92, in their farmhouse in Mansfield. On February 10, 1957, Wilder succumbed to the diabetic complications that claimed the lives of two of her sisters. She died at the age of 90 in their Mansfield home. Rose Wilder Lane died on October 30, 1968 at the age of 82 in Danbury, Connecticut. All three of them are buried alongside each other in Mansfield Cemetery.

According to Fraser, Wilder’s complex life can be seen as a great play composed of distinct, influential acts. Wilder bore her role as one of America’s greatest authors with ease, leaving behind a literary legacy that speaks for itself.

“As I say in Prairie Fires, her life falls into three acts, like a play: There’s the very dramatic first act of her childhood, when she experiences all the adventures and disasters that she writes about in the Little House books,” Fraser said. “But then there’s a profoundly important and tragic second act — the catastrophes of her early married life, when she and her husband, Almanzo, lose crop after crop to bad weather, go deeply into debt, and fall ill with diphtheria. It’s at that time that her husband is left permanently disabled by a stroke. Then they lose their second child shortly after his birth, and their house burns down. All of these losses set them on a path away from Dakota Territory. That exile from her family, I argue, is the event that ultimately inspires her desire to write her childhood. And finally, there’s her difficult but triumphant third act, as she becomes a writer during the Depression, helping to save their fortunes and memorialize her parents. It’s all a wonderful story, but for me, it’s her extraordinary persistence in that second act of her life — her bravery and tenacity in facing down loss after loss — that truly stands out.”

Wilder once stated: “Remember me with smiles and laughter, for that is how I will remember you all. If you can only remember me with tears, then don’t remember me at all.” In truth, Wilder’s legacy can only be remembered with smiles and laughter, for that is exactly what her books teach — the eternal power of seeking joy in the simple, heartwarming facets of life.