As Henry Starr entered the Stroud National Bank, he calmly pulled a revolver from his holster and leveled it at the teller, his accomplices corralled the frightened patrons and took three hostages. Starr grinned at the teller and demanded everything in the safe, it was a phrase he never got sick of repeating, and indeed, he found plenty of opportunities to say it over the course of his 32 years as an outlaw.

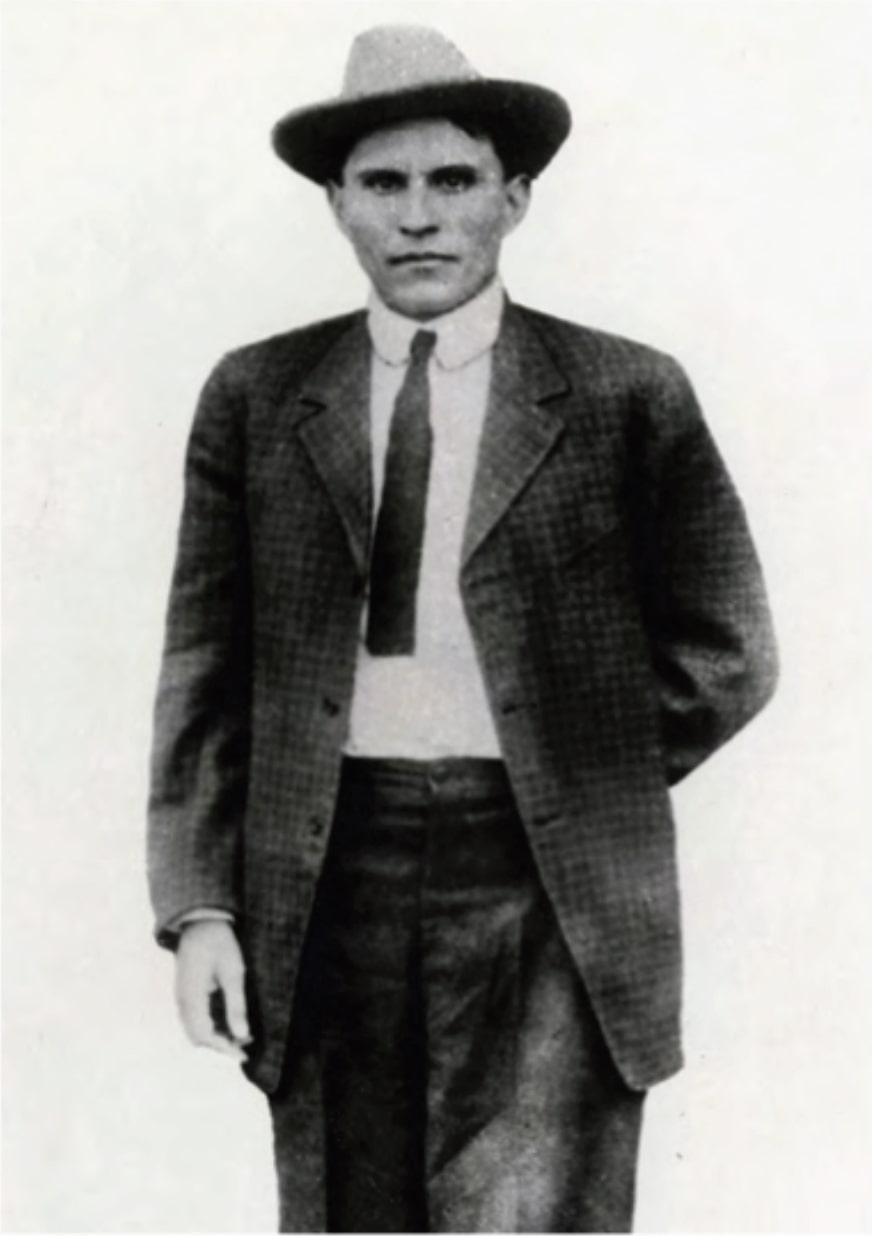

The world that greeted Henry Starr when he was born to mixed-race Cherokee parents George "Hop" Starr and Mary Scott Starr on December 2nd, 1873, in Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, was filled with turmoil. Henry spent his early years at his grandfather Tom Starr's feet, absorbing his stories of running whiskey and his bloody guerrilla campaign in the Cherokee Civil War. “[Tom Starr] was a fierce guy. It was said that his fists alone were lethal weapons and he could kill a man with one blow from his fist," recounts acclaimed historian and author Michael Wallis. The Starr family had come to Oklahoma before Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, an event where, as Wallis relates, "At the point of bayonets the Cherokee were force-marched West and placed into what is now the State of Oklahoma." Thus was the Oklahoma Indian Territory born, out of a Trail of Tears.

Henry Starr grew up in the Osage Hills near Tulsa, often referred to as “Robbers' Roost" by the locals. The rock hewn forests provided sanctuary to bandits and smugglers, including the infamous Belle Starr "Queen of the Outlaws" and wife of Sam Starr, Henry's uncle. However, Starr was quick to tell anyone who asked, that Belle was his aunt "...by marriage only," as he found her manner crude and repulsive.

Starr was not your typical outlaw; he didn't drink or smoke, he even abstained from coffee and tea. He was soft-spoken and made friends easily, but the association of the Starr name clung to him and made him a target for the Indian Police. As Richard Slotkin, historian and author of the novel The Return of Henry Starr, relates, "The Starr's were on the weaker side of intra-tribal political conflicts, dating back to the time before the Trail of Tears. They opposed John Ross, titular head of the Cherokee Nation." At 16, he was twice charged for horse-theft without evidence and locked up in Fort Smith, Arkansas. The Fort Smith prison, referred to as “Hell on the Border," by the inmates, lived up to its name. Hundreds of men were crammed into two underground rooms that had no natural light, no ventilation, and no separation between the inmates. His cousin was able to scrape together enough cash to pay his bail and the pair split town. “For Henry, choosing an outlaw way of life was a viable, even honorable response to perceived injustice and persecution," explains Slotkin. Starr himself would remark, "I preferred a quick and unostentatious internment in a respectable cemetery, than a life on the Arkansas convict farm."

Henry assembled a gang and began robbing stores and railway depots across Oklahoma in a series of brazen daylight robberies. At night the band would hide out in the Osage Hills north of Tulsa, boasting of their adventures with the other outlaws. Henry Starr seemed uncatchable, giving Marshalls and Indian Police the slip on multiple occasions. In 1892, he was nearly captured by Deputy Marshall Floyd Wilson near Wolf Creek. In the shoot-out that followed, Wilson was killed, adding murder to the charges accumulating behind Starr. His bold daylight robberies and frustrating elusiveness made him a household name, and soon his striking dark features were plastered across the state, offering a reward of $5000, equivalent to about $130,000 today.

Despite the law being hot on his trail, Starr and his friend, Frank Cheney, decided to up the ante, robbing their first bank in Caney, Kansas, on March 28th, 1893. They burst into the bank at mid-day, each brandishing a pair of Colt revolvers. While the robbers corralled the customers into a stockade, a cashier broke from the group and sprinted into the manager's office. Starr gave chase. He relates the stand off in his autobiography Thrilling Events: The Life of Henry Starr: "He had his hand on a big Winchester, but I shoved both pistols full cocked into his face, he dropped his before I could command him to do so." The thieves made a clean escape out the back of the bank and were galloping hard into the hills by the time the alarm was raised. The rush of the caper had a tremendous effect on the young man; robbing banks gave a thrill unlike anything he'd experienced, it fast became an obsession.

However, Henry's luck soon ran out. He was captured in Colorado Springs at the Spaulding House on July 3rd, 1893, and returned to the black hole of Fort Smith. Twice he was sentenced to hang by the neck, but his lawyer was able to appeal the decisions. Eventually, he pled guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced with 15 years. He ended up serving only eight years of his sentence as he was well-behaved in Tulsa prison and even helped the guards contain a jailbreak by convincing an armed prisoner to surrender.

In 1901, he was pardoned by President Roosevelt and released. Following his departure from incarceration he made an honest living working in his mother's restaurant. He married in 1903 and had a son, whom he named, Theodore Roosevelt Starr.

Henry tried to make a go of the simple life, but Arkansas authorities were still clamoring for his extradition, unsatisfied by his light sentencing. He fled to the Osage Hills and fell in with his old compatriots. In 1908, he crossed the border into Kansas and began a new spree of robberies. This run would not last however, as he was soon captured and sentenced to seven years in Canon City, Colorado. He served five years before being paroled in 1913, on the condition that he didn't leave Colorado.

Of course, Starr only followed the law when he was in prison. Upon release, he immediately crossed back into Oklahoma and began his most daring spree yet: pulling off 14 daylight bank robberies between 1914 and 1915 across the state. Marshalls turned over every rock and shrub in the Osage Hills trying to find Starr's hideout. They grilled his known accomplices for information and offered a $1000 reward for him, “Dead or Alive." Henry was, in fact, hiding in plain sight, in an apartment block in downtown Tulsa, just two blocks away from the county Sheriff, as Slotkin illuminates: "A dusty part-Indian cowboy riding into town was too ordinary a sight to attract much attention.”

The spree culminated in Stroud and a daring double daylight robbery, a feat previously attempted by the Dalton Gang in Coffeyville, Kansas, in 1892, where the gang had been wiped out. As the Stroud National Bank teller emptied his till into Henry's burlap sack, a surge of confidence flooded the outlaw's body: was he really going to get away with it?

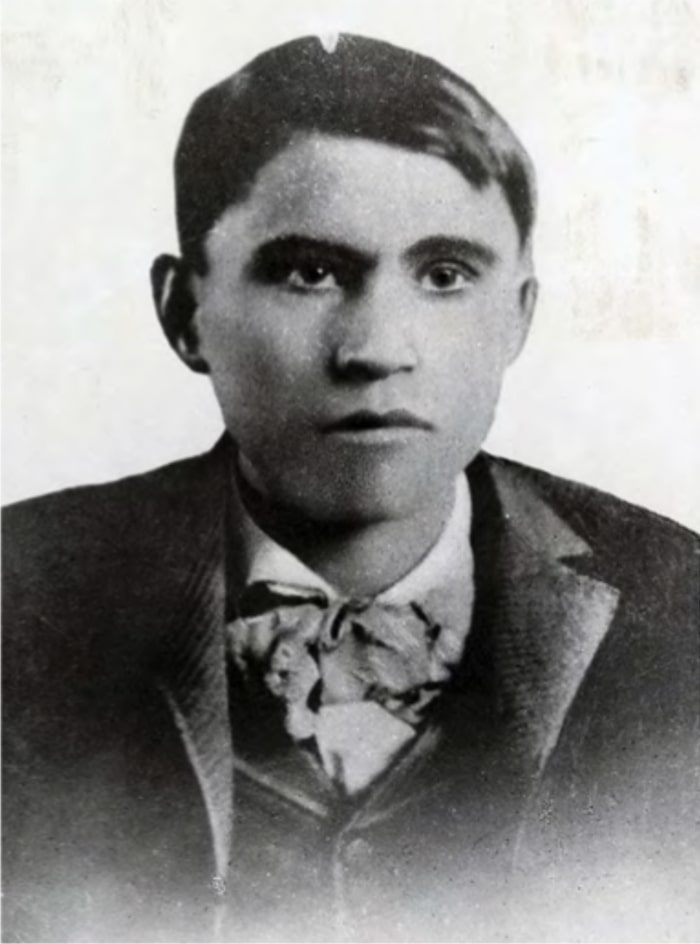

Word of the robbery had spread quickly around the small town. As the gang charged out of the bank and regrouped with their compatriots, bullets began to wiz. The citizens of Stroud took up arms against the bandits and turned the quiet streets into a cacophony of gunshots. They fired from shop windows, grocery stalls and saloons, forcing the gang to scatter. Twenty year-old Paul Curry brandished a short-barreled shotgun his uncle used to butcher hogs and incapacitated Starr and his accomplice Lewis Estes. The rest of the gang made off with $5815.

Starr recovered from his injuries, but was sentenced to 25 years in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. As usual, however, his good conduct behind bars and fervent renunciation of the life of crime impressed the prison officials, and he was released in 1919, having served only four years of his sentence.

This time, however, Starr was determined to stay straight. He parlayed his infamy into a successful acting career.

In 1919, he produced and starred in A Debtor to the Law, a film re-creation of the Stroud heist. Starr described the film as a way to exercise his criminal past and “confess" his crimes. He returned to Stroud to film the picture and enlisted the townsfolk who had foiled his robbery to recreate it on film, including the bank teller he'd robbed and Paul Curry, the boy who'd shot him. The film was a local sensation, Starr was even offered a role in a Hollywood movie, but turned it down for fear that California officials would extradite him to Arkansas.

In 1921, Henry Starr's life was more comfortable than it had ever been; he remarried and bought a house in Claremore, Oklahoma, making a steady income on his movies. But after two years of calm, he became restless again. He craved the rush of the heist, the challenge of planning, and the thrill of execution. On February 18th, 1921, he drove into Harrison, Arkansas, with three accomplices, to hit the People's State Bank. "It is said to be the first time an outlaw showed up to a bank job in an automobile," illuminates Michael Wallis. "While they collected their $6,000 in loot, the former bank president slipped into the vault, grabbed his Winchester, and opened fire. One slug slammed into Starr and severed his spine, the others fled empty-handed."

Henry was rushed to the county jail for treatment. The doctor was able to remove the bullet, but Starr's wound was mortal. As his life ebbed away, he gasped to the doctor: "I've robbed more banks than any man in America." He died the next morning, February 22nd, 1921.

Indeed, he had robbed 21 banks during his outlaw career, more than the Jesse James Gang and Dalton Gang put together. Henry Starr made off with nearly $60,000 during his 32-year reign, an equivalent of about $1,500,000 today. Much of this stash was never recovered by authorities and is reportedly hiding somewhere along the Cimarron River in Stevens County, Kansas. Starr described the spot as "...near the border in a place nobody could find it in a million years." Visitors to the southwest of Kansas may benefit from a closer look along the banks of the river.

However, the money was not what pushed Starr into a life of crime, as Richard Slotkin describes: “[Starr] thought of himself as what social historians call a 'social bandit’-an outlaw who acts on behalf of an oppressed social group or community against the dominant group." Victimized by the law from a young age, Starr saw banditry as his only salvation against injustice. As he related in Thrilling Events: The Life of Henry Starr: "Privately, I don't believe completely in anything that has or ever will happen; only in the inexorable law of total obliteration and nothingness."

He was the last of the horseback outlaws. As cars became ever more affordable, highways spread into the remote wilderness that he once called home. In 1926, five years after Starr's death, Route 66 was designated, and Stroud turned from a tiny backwater into a bustling way station. Tulsa was transformed from a rough cow town to the "Oil Capital of the World". The legacy of the bank robber would continue, but on tires rather than hooves, as the Old West died and roadside America dawned.