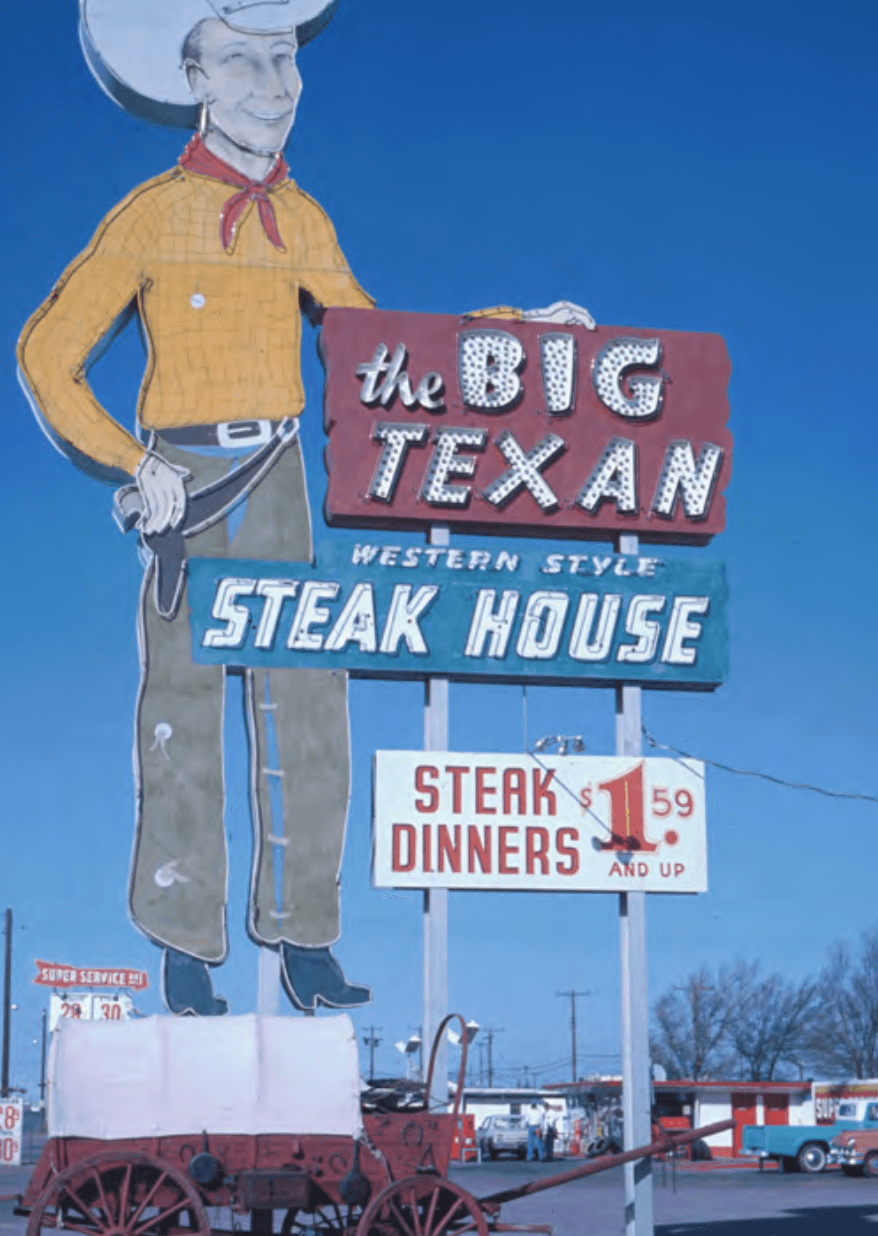

This is The Big Texan Steak Challenge, one of the most famous eating contests in America, and it has been enticing people from all over the world for over 50 years. Some might say it’s just a kitschy tourist-trap, but behind The Big Texan’s bright yellow exterior and over-the-top persona lies a struggle for success, a tribute to Texas’ Western roots, and a family legacy tied to Route 66.

The Mother Road was aligned through The Lone Star state in 1926, running from Texola to Glenrio across the Texas Panhandle, with Amarillo at its heart. Unlike other Route 66 states that have jutting mountains and vast canyons, the panhandle is as flat as a pancake. But the wide-open plains and expansive blue skies have their own type of majesty; some claim that during an Amarillo sunrise and sunset you can see the curvature of the earth because of the almost limitless view afforded by the even terrain. Bob Lile, artist, historian, preservationist, and member of the Historic 6th on Route 66 Association (they work to preserve the historic Route 66 district in Amarillo), notes that the Texas stretch of Route 66, the second shortest after Kansas at 178 miles, might not have the prettiest scenery; “But, we’ve got the friendliest, best people along the whole route. And we’ve got some really good history too.”

An important part of that history began, and still lives on, in Amarillo: the place Lile calls the unofficial capital of Route 66 in Texas. The southern plains meet the desert in Amarillo, and the wide-open spaces provided the perfect place to raise large amounts of cattle. In 1893, Amarillo’s population was listed as “between 500-600 humans and 50,000 head of cattle.” A few years later, Amarillo had become one of the world’s busiest cattle-shipping points, and that heritage lives on today; Amarillo is the beef capital of the world, with over 1 million head of cattle and many large ranches, including the still-running JA Ranch founded in 1877. Today, you can still find cowboys gathering their cattle by horseback. Eric Miller, Director of Communications at the Amarillo Convention and Visitor Council, says the town is very proud of its Western heritage. “We really are the Texas that many people grow up thinking about, with ranches and cowboys and pickup trucks, horses, it all exists within 15 miles of our downtown.” Route 66 helped bring visitors to Amarillo hoping to capture the authentic Texan experience, and The Big Texan Steak Ranch is a big part of that. Miller notes that Amarillo has 2 to 3 million visitors per year, and The Big Texan and Route 66 are two of the biggest draws. But originally, it began with a man wanting to make a better life for his family, taking America’s highway to Texas to experience true Western hospitality.

It All Started With a Dream(er)

R.J. Lee was living with his wife, Mary Ann, and their young children in Kansas City, Missouri, when they decided to move to Amarillo in 1958. R.J. had grown up enthralled with Texan cowboys and ranchers, and with a young family to support, he saw Amarillo as the ideal place to experience the Lone Star atmosphere while laying down roots for the future. While Texas lived up to his dreams and more, the one disappointment he had was that he couldn’t find a first-class Texas-style steakhouse in the area. So, R.J. decided to build it himself, right on Route 66.

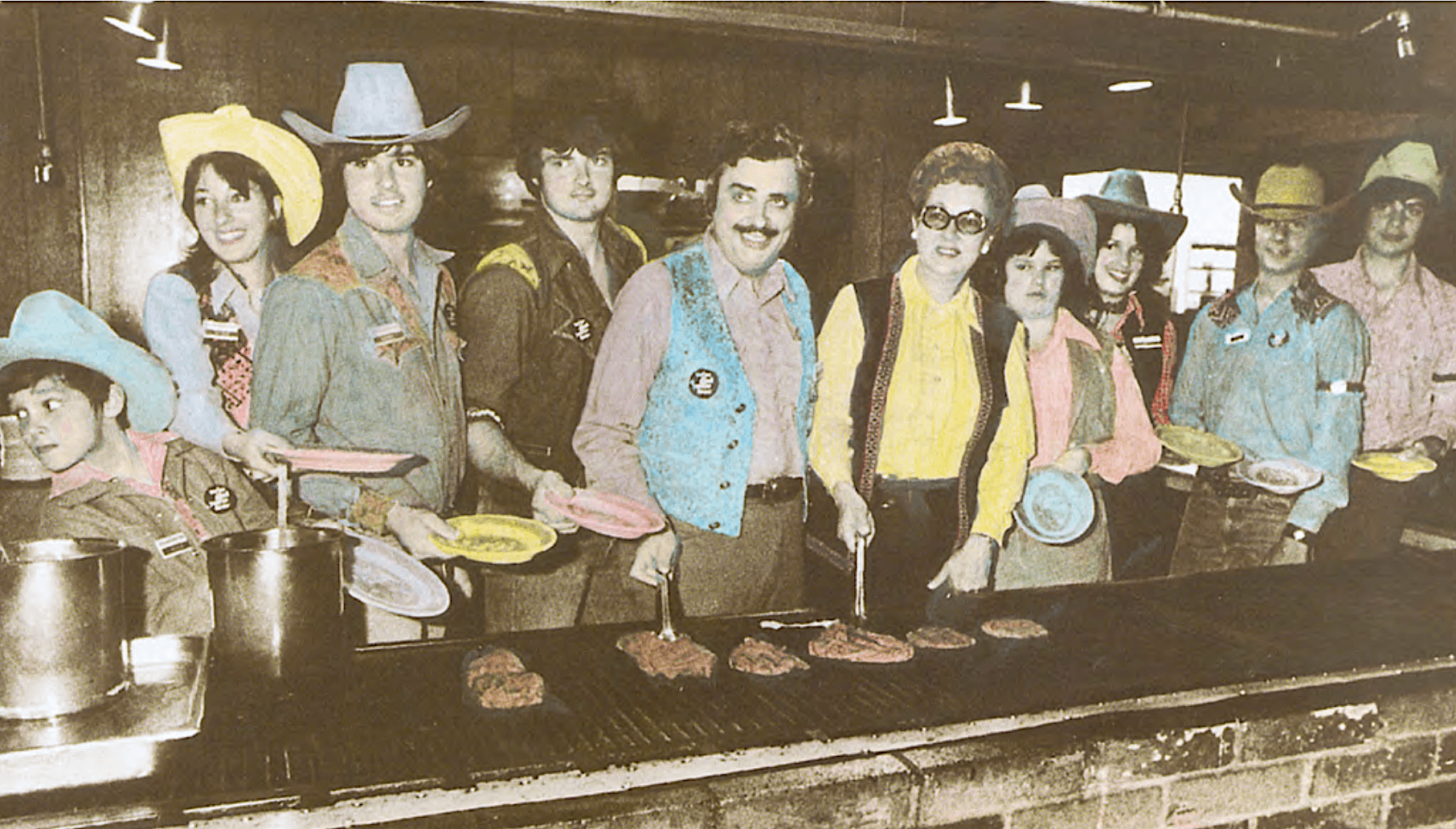

This was in 1960, and the Mother Road’s revival hadn’t begun yet. For R.J., Route 66 was simply the highway that went through Amarillo, from which he could attract tourists. As Bobby Lee puts it, son of R.J. and Mary Ann and co-owner of The Big Texan today, if you’re in the boat business, you need to be on the Mississippi River. If you’re in the hospitality business, you need to be on the highway. But simply being located on Route 66 wasn’t enough; R.J. had to offer visitors an authentic taste of Texas that would draw them in and keep them coming back. “My dad didn’t have a real good grip on what a real cowboy was or wasn’t until he started working with the area’s stockyard producers,” Bobby elaborates. R.J enticed local cowboys to stop in after work by offering big, juicy steaks and an ice-cold beer. He also knew that they would be the big draw for tourists, so he reserved a huge 12-person table for them in the middle of the dining room, center stage for the cowboys to show off their bravado and antics to the other diners, while he plied them with excellent food and drink. Bobby adds, “I remember as a kid watching him see the reaction in the diners, how powerful it was whenever they would see a real cowboy ... That was the whole scheme behind The Big Texan originally. Bigger steaks and bigger cowboys.” Little did R.J. know just how big the steaks would get.

The Birth of the Biggest Challenge Around

The cowboys at The Big Texan spent their evenings challenging each other’s virility – whether it was who ate the most food, drank the most beers, or had the bigger muscles, the cowboys loved a challenge. One Friday night in 1962, R.J. pushed a few tables together in the middle of the dining room and challenged his favorite patrons to the ultimate contest. Whoever could eat the most one-pound steaks in an hour would win, and get his dinner for free. One ambitious hostler ate four and a half one pound steaks (72 ounces), and complained that he was still hungry, so R.J. brought him a baked potato, shrimp cocktail, salad, and a bread roll.

This seemed to hit the spot, and when he was finished, R.J. announced that anyone who could eat what that cowboy just ate would get their meal for free. Bobby recalls, “My dad never thought he would have a taker, but the next week we had two cowboys come in wanting to try the thing, and the place went crazy!” Tourists were talking about it, the newspaper came out and took pictures, and an immemorial challenge was born.

To this day, The Big Texan gets three to four challengers a day, notes Danny Lee, co-owner of The Big Texan and younger brother to Bobby. They’re approaching 100,000 steaks served, and only about one out of every nine challengers finish the steak. The odds are better for women about one in two, adds Bobby: less women overall take the challenge, but the ones that do are very confident, and not egged on by ego or dares. In fact, the record-holder, Molly Schuyler, a 120-pound mother of four, ate three of the 72-ounce steak dinners in twenty minutes.

When asked if he had ever attempted the challenge himself, Danny admits, “When I attempted it, I failed miserably. Bobby ate it and we went out and played racquetball and he still beat me in the game.”

Bobby and Danny spent their childhoods living and working at The Big Texan. In the early years, playpens and bassinets filled the kitchen, and when they got older, they were put to work. When they were four and five years old, they learned how to wrap baked potatoes, peel shrimp, and buss tables - all for a dollar a day. The first head chef, Mr. Vance, gave them kitchen assignments that they completed while standing on vegetable crates to reach the counters. All holidays were spent working at the restaurant, including Thanksgiving and Christmas. Danny notes that, “Still to this day, my kids and my wife, Bob’s kids and Bob’s wife, we all go to work on holidays.”

What is now a privilege and part of maintaining a legacy became a relentless chore for the young brothers. Bobby excelled in athletics so that he could go and play sports after school, instead of going to work at the restaurant, and both boys left Amarillo after high school, searching for purpose outside of the restaurant business. “The second I got a chance to get out of town, I got out of town, and stayed away,” recalls Bobby. He went to college and Danny got into electronics after graduating in 1979 and worked for a big company in Dallas for a number of years.

A similar uprooting happened to The Big Texan a decade earlier, when Interstate Highway 40 replaced Route 66 as the major thoroughfare of the country in 1968.

Overnight, business at The Big Texan came to a halt. “One day he had a full dining room and the next day there were two people for the whole day,” says Bobby. But R.J. had eight kids to feed, and he had to adapt to survive. Unable to get a loan from the bank, R.J. took his sons out to an old army barracks they owned and they pulled it apart, piece by piece, preserving every scrap of lumber and nail to rebuild The Big Texan along the I-40. The new restaurant, where the current one stands today, was built out of love, tenacity, and desperation. Danny recalls his father driving by newspaper stands, asking if the local boys needed jobs, thus he rounded up a bunch of day laborers and built The Big Texan from the ground up.

R.J.’s limitless reserves of tenacity were tested frequently: he attempted to open another restaurant in Lubbock, Texas, in 1975 to appeal to the Texas Tech crowd, but it was unsuccessful and closed after two years; and, The Big Texan built out of scrap lumber, burned to the ground in a fire in 1976, except for a banquet room that was built in 1972. However, R.J. always adapted, and The Big Texan re-opened shortly after and continued to be a smashing success.

Passing the Torch

After spending most of the 80s in Dallas, Danny moved to his father’s hometown of Kansas City to work with his uncle at the Savoy Grill, an upscale dining landmark in the city since 1903. Danny had always loved working in the kitchen, and rediscovering his family’s roots caused him to fall back in love with the restaurant industry.

On a cool Sunday afternoon in 1990, February 4th to be exact, Danny had gone to see a matinee movie with his wife, but he remembers feeling weird all day. He had an apartment in the Savoy Hotel above the restaurant, and the phone was ringing incessantly. He ignored the phone because he thought it was just another call about inventory, but finally someone came to his door to tell him that his mom was on the phone. R.J. and Mary Ann were in Hawaii on vacation with some fellow restaurateurs at the time. His mother told him that his father had died of a heart attack while swimming in the ocean, spending his last moments on earth enjoying the warm water, The Big Texan far from his mind. All of a sudden, Danny went from talking to his father on the phone every day to losing his father unexpectedly at the age of sixty. He believes that it was all the hard work that did his father in, the stress of numerous setbacks and pushing himself to succeed for the family he loved. “And he just, he just didn’t stop,” says Danny, “He didn’t stop.”

When Bobby heard the news of his father’s passing, he decided to move his family back to Amarillo and continue his father’s legacy. Bobby and his seven brothers and sisters were consumed with grief and confusion after their father’s sudden death, making it difficult to know what needed to be done to preserve The Big Texan, so Bobby stepped into the leadership role. Knowing Danny’s extensive experience at the Savoy Grill, Bobby knew he could bring a lot to the table, and so Danny moved back to Amarillo to be co-owner of The Big Texan in 1997.

Opposites Attract

Bobby and Danny’s combined experience and distinct skill sets create a special sort of magic for The Big Texan, and the family legacy not only continued to succeed, but expanded and flourished under their leadership. And it was a key lesson Danny’s uncle had taught him at the Savoy that laid the groundwork for their unparalleled hospitality: “Always take care of the next person in the front door, and everything else will fall into place.”

They may sometimes fight like brothers, but Bobby and Danny also succeed because they are opposites. Danny describes it as the combination of internal marketing and external marketing. Bobby focuses on promoting the restaurant and keeping the legend alive, whether it’s with billboards or social media. Meanwhile, Danny focuses on service, making sure salad plates are cold, dinner plates are hot, the steaks are aged properly, and bought at a competitive price. As they explain it, Bobby keeps them on the front page and Danny keeps them off the obituary.

Ultimately, the foundation of their success is keeping alive the mystique of the cowboy that their father first started. “The cowboy never goes out of style,” remarks Danny, “and do we embellish about the cowboy and make it bigger than what it is? Hell yeah we do! You know, big steaks, we got a big boot that’s two stories tall, we have a rocking chair that you can get 23 people into ... Do people get up on the table and drink whisky and dance? Well, if that’s what people want to see in Texas, then hell yeah we do it. You know, we give people kind of a blank canvas and let them draw in what they feel Texas is, and what we do is deliver it.” Or, as Bobby puts it, “It’s always the real deal and it’s cozy and right in your face with it.”

Ingenuity and Expansion

Bobby thinks that if his father could see what The Big Texan has become today, he would be really surprised at the national and international audience it has developed, as well as how much the business has expanded. The Big Texan compound now includes a motel designed to look like an Old West main street, an RV park, an outdoor concert venue called Starlight Ranch, a brewery, and a fleet of limos to bring customers to the restaurant. It is this entrepreneurial ingenuity that keeps The Big Texan successful and ahead of its competitors. But while everything is changing, everything is also staying the same.

“I remember as a kid the smell of the cocktail sauce,” says Bobby. “I remember the taste of the salad dressings and it’s still the same. Everything is expensive as hell to make, but you know, it’s about those people when they taste it, they say, ‘You know, this is exactly how I remember this thing.” Keeping that original quality is one of the most rewarding parts of the business for the brothers, and it’s what keeps customers coming back.

Bobby and Danny both have adult children of their own now, but they are not pressuring them to join the family business. Most important is allowing them to spread their wings and have new experiences like they did once, because a return home is all the sweeter when you’ve been away and choose to come back.

But what does it really feel like to be a caretaker of an internationally-known Texas legend? “I’ll answer that in a strange way,” replies Danny. “Kansas City, this one kid that used to deliver food to us, he was a purveyor, and he told me one time that one of the jobs he had before was climbing those real tall radio towers and changing the light bulbs on top. And he said sometimes it’d take him three or four hours to climb all the way to the top, and then when he got to the top, the view was spectacular. And I always likened it to that, it’s a real tall ladder, and you start on the first rung at the very bottom, then you go to the second rung and you go to the third one. Then, sometime you look down and you realize you could die if you let go. You know, you’re so high; you’re high enough where it’s dangerous. And you keep on climbing, and you just don’t look down and all of a sudden one day you happen to look around and you realize that you’re above the clouds. You can see forever. Then one day we realize we’re not really owners of this business, we’re curators.”

As Bobby adds, “It’s a one of a kind place, you don’t see this kind of place very much and when you do, you get that feeling that it’s a landmark, you’re going to do something special.” And do something special they did.

To the Brink and Back

After completing the 72oz Steak Challenge, winners get a chance to leave a comment for posterity, as recorded in the Hall of Fame on The Big Texan’s website. Some did it for family: “Father-in-law challenged me to do it.” (Chuck Barsness, 1975); “Had to call my mom to get encouragement.” (George Rutherford, 1988); “My son will be back in 20 years.” (Greg Schrop, 1997). Some became philosophical: “The will to succeed is the first condition of victory.” (Richard E. Primeau, 1987); “You define the moment and the moment defines you.” (Paul B. Thacker, 2003); “Vedi, Vidi, Vici. (I came, I saw, I conquered.).” (Jason Apodaca, 2011). While others found a sense of humor: “A steady chew got me through!” (Ken Wareham, 1976); “I thought it would shrink when it was cooked.” (Steve Evans, 1982). Many claimed to have turned vegetarian over the incident, and it provided a once in a lifetime experience for others. But, the most common comment has been, in fact, a question: What’s for dessert?