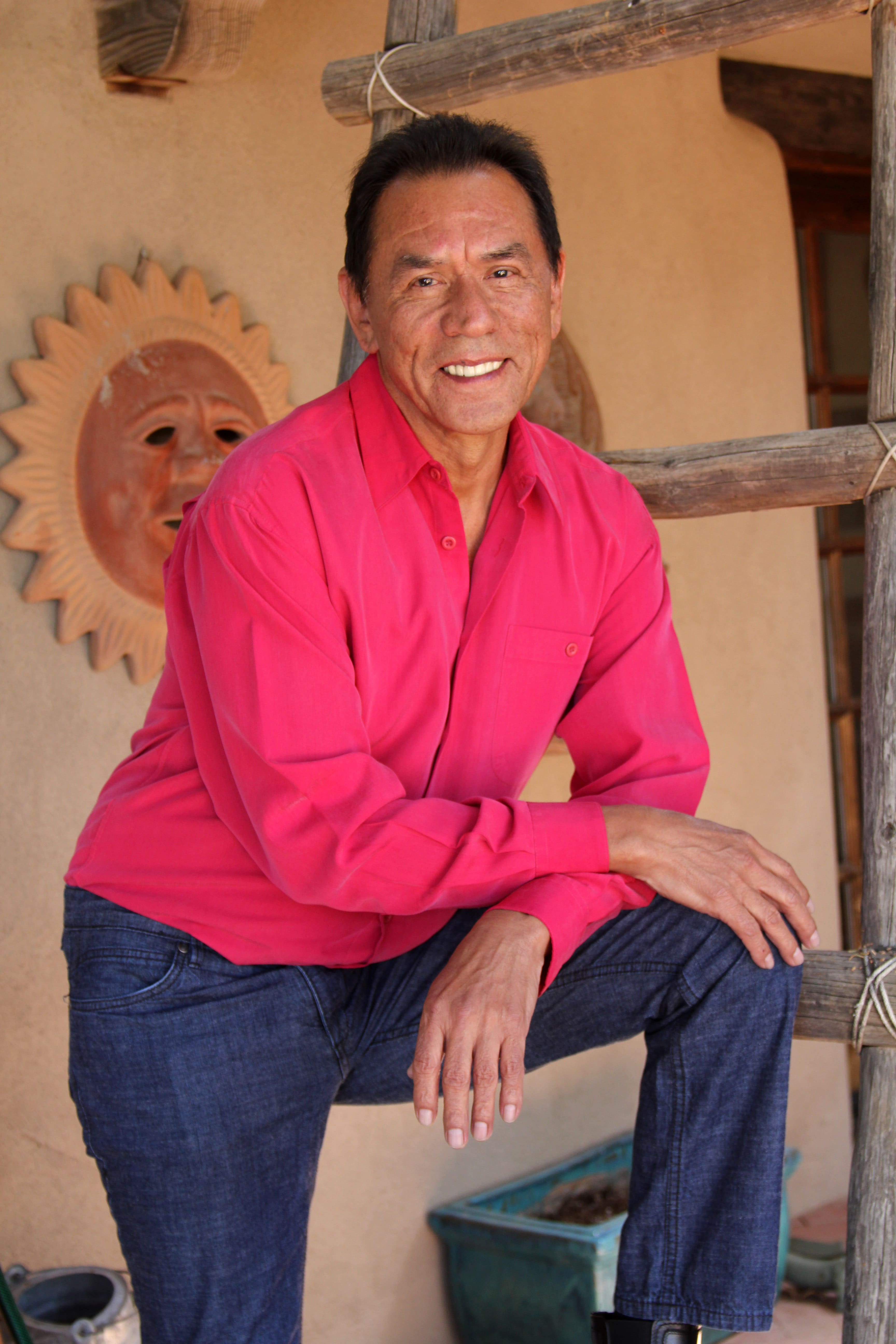

You were born in 1947, in a place called Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma. What was your childhood like?

Well, my first five years of life were pretty much centered around Nofire Hollow, which is... it’s a country term. It’s not really a place, it’s just a home between the towns of Stilwell, Oklahoma, and Tahlequah. And it’s way out in the country. I lived the farm life, you know, hunting, subsistence, and growing agricultural goods... life in an extended family situation.

We moved from Nofire Hollow when my dad came back from military service. He had studied agriculture, farming, and ranching in high school, so his work took him to several farms and ranches, mainly in the northeastern part of Oklahoma. Small towns like Avant and Skiatook, and finally Collinsville.

Because of my father’s work, we pretty much stayed to ourselves, except when we went back to visit with family in Nofire Hollow... it’s actually Cherokee Nation, it’s the northeastern 14 counties in the state of Oklahoma. And while we lived within or near its borders, we didn’t really have any kind of social life living in those areas that were mainly made up of non-Cherokee, non-Indian people. So, our life was fairly isolated and pretty much to ourselves, except for the fact that I did have to go to school and such.

Until I went to high school, it was pretty much a solitary kind of growing up. I really didn’t associate that much with people outside of our immediate circle, which were, you know, people who worked the same ranches that the old man did.

Did you go to a mixed high school?

No, I went to an entirely American Indian high school, which was a boarding school called Chilocco Indian Agricultural School. There were tribes from all over the United States there, from New York state to Florida to the Dakotas, the Northwest, the Southwest, there were Indians from everywhere. It was a revelation to me that there were that many different kinds of Indians, to tell the truth.

When you were growing up, was there an openness in the Cherokee Nation to embrace non-Cherokee culture as well as to welcome non-Cherokees into a better understanding of Cherokee culture, language, history, and etc.?

It was [more] a matter of we were Cherokee and they were not, and it was a pretty distinct line between the white population and us. And it was pretty much, ‘never the two shall mix.’ You know, back then, I think the miscegenation and laws were still in effect and there were also towns wherein they had the Green River Ordinance, which was really, ‘Stay out of town if you’re brown.’ After a certain time, like 7 o’clock or dark or whatever. But yeah, it was fairly segregated. I think social life was fairly segregated back then.

Do you think that Oklahoma has become much more of a multicultural state? Have you seen much of a change back in the Sooner state?

Yeah, I think there’s been a change, you know, because of the Civil Rights Movement, as well as other factors. There’s been a huge change in terms of the Cherokee standing and what is Cherokee Nation at this point, simply because of the fact that Cherokee Nation itself, when I was growing up was, it was fairly nonexistent, it had practically nothing to offer other than... I really don’t know what it had to offer as a child. But by the time of the 70s or thereabouts, it began to grow to the point that it is now probably the most efficient economic machine within the 14 counties of northeastern Oklahoma. I mean, it hires more people... it’s an economic machine within the state. And so, that has changed a lot of attitudes toward Cherokee people and has promoted more mixture between the races, if you will, and more working together on political and social issues. There has been a change simply because of the growth of the Nation itself, on a political platform.

In a 1993 Entertainment Weekly interview you said, “I’m a Cherokee first and an American later. And while I may forgive, I’ll never forget. I’m gonna pass those feelings on to my own kids.” Do you still feel that way today?

Absolutely, nothing has changed as far as that goes. I stand by that, yeah.

Do you feel that that is a sentiment that a lot of Cherokee would actively support or embrace? Cherokee first, American second?

I think that a lot of people do identify with their own people, if you will. I think it’s just simply inherent in all of us, that we know who we are and where we come from and we also know history.

Given your current and past work as a Native American activist, and as an actor who has played countless powerful Native American roles, what do you feel about the current path that Hollywood is heading in terms of representation of Native Americans in film and TV? Are we heading in the right direction?

I think we’re probably heading in the right direction, yes, but this business is a very unpredictable creature and it depends on the whims and interests of audiences looking for entertainment. I don’t know if it’s a great incentive to be more inclusive on a social plane, but I think that, at this point, social pressure has gotten Hollywood to think about telling stories that are more inclusive of different ethnic groups and minorities.

You’ve played a lot of very iconic Native American roles in some very respected films. How important is it for you to step outside of the ethnic identity when being cast in a role?

I’d love to get to the point where I’m considered simply an actor, a working actor, if you will. (Laughs) And personality and all of that aside, you know, celebrity and all of that aside, I think that we as actors simply like to perform any and every kind of role that interests us, and that’s what my goal is, and I will continue to work towards it.

In many ways, starring in The Last of the Mohicans as Magua catapulted you to stardom and a very enviable level as an actor. Was fame something that you actually, at that stage of your career, were looking for?

That was difficult, I’ll have to tell you, it was difficult, and for a while I kind of fortressed myself against the idea of celebrity and fame and sort of said to myself and anyone who asked, ‘No, I think the craft is what I’m more interested in.’ But on the other hand, in order to continue to practice the craft, one needs the attention of filmmakers. So yeah, it’s kind of an obstacle that one has to come to the point of accepting or not.

I don’t think you can rail against being popularized by the press or against any other kind of attention that you receive, simply because you have to have the publicity in order to acquire the work, most of the time. If people don’t know about you, then more than likely, you’re not going to find work. It’s a never-ending cycle.

You moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the early 90s and Mohicans came out in ‘92. Did you find Santa Fe a good place to take cover and a safer landing spot to live your life with a bit of privacy at that point?

Well, I think the main purpose of moving to Santa Fe at that point in time was a matter of where we were going to raise our son and we moved here right after Geronimo, yeah that was in ‘93, and my wife, Maura, was pregnant with our son Kholan. Rather than go back to Los Angeles after Geronimo, we decided Santa Fe was an area that was almost in the middle of the map in terms of where Los Angeles is and where northeastern Oklahoma is. And so, as far as family is concerned, my wife is from LA and I’m from northeastern Oklahoma. Santa Fe is right in-between, so we moved here.

The irony is that as soon as our son graduated from high school, he moved to Los Angeles. (Laughs)

Isn’t that always the case!

Yeah, it sure is. (Laughs)

The fight scenes in The Last of the Mohicans must have required a lot of practice and choreography.

To prepare for and to execute, yes. (Laughs) They were very well choreographed, and we had some good people to work with in doing that.

When you are creating a character like Magua, who is filled with so much raw emotion and hate, do you carry the character with you: their emotions and sentiments throughout filming of the picture, or are you able to leave the character behind when the director says, ‘Cut’?

Well, during that time, which was probably around my fourth time in front of the big cameras, (Laughs), I found it very difficult to immediately come out of whatever scene I had just done. Feeling the kinds of emotions that you have to bring to the fore for characters like [Magua] who were very intense in terms of what they were accomplishing in their roles... It’s very difficult to come out of an extremely emotional scene. So no, I would simply stay away from people for a while until it kind of wore off and I was back to normal now. (Laughs) Until the next time I do it.

But as time goes on, I think most actors get to the point where they can deal with these emotional scenes and be able to come out of them easier or quicker.

In recent years you’ve heard people speak out against what they would define as cultural appropriation. What are your feelings about that?

Cultural appropriation is, oh that’s a very fluid concept, if you ask me. I don’t know if it’s a matter of people taking advantage for their own advantage or to capitalize on someone else’s idea… I don’t know that it’s something I have a handle on. You know, whenever cultures do come together, things are traded and things are negotiated, it’s just difficult to define exactly what it is.

You know, the matter of mascots for one thing is something that has something to do with our cultural appropriation argument. I have to kind of step back and tell you that on a personal level I think it’s disrespectful, I think it was born of an idea that we as Native Americans, American Indians, whichever you would use, were less than human in our existence and we were seen that way or that we were childlike people who needed to be guided through life. In any case, we were put down.

I think whenever you see some non-Indian guy jumping around, acting in a manner that he thinks we act in... that part of it I personally have a problem with. I don’t think that the idea of using the name of the Washington Redskins is any great honor bestowed upon any Native American, because of where the term actually comes from. It’s from our scalps, our noses, our ears, or whatever was used to prove bounty. On the non-Indian’s part, that’s a repudiation of what they actually did. It’s a repudiation of a genocide, an attempted genocide and I think they should be much more aware of what their actions evoke. I think we all need to look into our own attitudes and actions and how we conceive of issues like this.

You’ve spent most of your life in one of two Route 66 states, which is pretty cool. In your younger life, were you aware of Route 66? Did its American identity stand out to you?

No, (Laughs) I had no idea of it. In fact, I lived very near the big Blue Whale. That’s in Cherokee Nation.

So, Catoosa is part of the Cherokee Nation?

Catoosa is and a large part of the northern part of Tulsa is Cherokee Nation and Claremore, that whole northeastern part of the state is mainly Cherokee Nation. But no, I had no idea of what Route 66 was until perhaps 1968 or thereabouts.

Have you ever gone to visit the Whale?

No, (Laughs) we just saw it from the road, it was close.

What did you think that huge blue whale in the forest was at the time?

Well, I think that generally, we just thought maybe it was an amusement park or something like that. (Laughs) I don’t ever remember stopping there, you know, so we really had no idea what it was, other than a park or a place to stop and maybe there was... maybe it was like a little carnival or something. But we were busy traveling. It was part of commercial America, as far as we knew, and we didn’t have the time or the money to investigate.

So, what brought Route 66 to your attention in 1968?

When I was on my way to Vietnam, that was in ‘68, I hitchhiked out to the [West] coast, to San Diego. Somewhere around Oklahoma City, I had been hitchhiking for a good day I suppose, and I wasn’t attracting anybody to pick me up. (Laughs) So I thought, “Well, maybe if I put on my uniform things will change.” So, I just took my duffle bag and, off the road, where I found some cover, I changed into my dress greens. I came back out onto the highway and stood in my uniform and duffle bag. And after a while, it was pretty quick actually, I was picked up by a family moving from somewhere in the southeast out to California. The little family was made up of an older woman, her daughter, and a son-in-law. They were going out to California to change their fortunes.

The first thing that they asked me when they stopped to pick me up was “Do you have a driver’s license?” And I immediately said, “Yes.” I didn’t tell them that it was a military driver’s license, that’s all I had at the time. But we drove from Oklahoma City to California. They talked a lot about Route 66 as we traveled. It seemed like quite a long trip, but we got to know one another. I actually even drove their car for a while, it was a big old station wagon, kind of old for that time period even. But in any case, yeah, that was quite a trip that we had out to San Diego.

Did you find a warm welcome when you returned home from Vietnam or was the response a little less grateful? 1969 was certainly a time of protests for the war.

I think that it was very significant that when I came back, we landed [back] in San Diego. The army themselves told us, at that point in time, they gave us vouchers to take to the PX to buy ourselves civilian clothes. They said, “It would be best if you traveled in civilian clothes rather than in your uniforms when you’re going home.” So that was a pretty good indication that we were not that welcome anywhere, really. (Laughs)

Do you feel like you have an understanding of the significance of the iconic highway now?

It was a big motorized expansion into the West, beyond railroads and all. And I know that it brought commercial opportunities for southwestern Indians who I guess really started the concept of trading posts, or they expanded those ideas, wherein they were able to commercialize their crafts because of tourists who passed through. I think it was the beginning of the Indian art market. The idea of a romantic Route 66 never entered our mind, it was simply a matter of travel. It was a practicality.

Do you still have an emotional connection to Oklahoma? Do you feel like you’re going home when you’re in the state?

Yeah, I suppose you could say that. But you know, I have my political differences with the state of Oklahoma. Otherwise, yeah, that’s the land where I come from. My family’s there. (Laughs) Everybody’s there.

You’re 72 now, you’ve been in countless films and projects, you’ve helped launch a newspaper, you’ve raised three kids, you’ve seen and done a ton of things with your life and your career and it doesn’t seem like you’re at any point Wes, to put your hat on the hook. Are there any things that are still on your bucket list at this point?

I don’t have a hook to hang my hat on at this point. I guess it’s a matter of what I’ll do, figure out how to build a hook for my hat. (Laughs) I’m not looking to do that anytime in the near future.

But I want to work towards the development of Native American filmmaking. I’m working towards a better representation in the overall industry and the growth of Native American filmmaking amongst our own. I think Oklahoma is beginning, as well as many other states... There are a lot of young native filmmakers who are beginning to develop, and I think that within my lifetime, we’re going to have some well-known professional native filmmakers who are going to be known as well as a Spielberg or a Cameron. So yeah, that’s what I’d like to work toward.