What or who influenced you to pursue a life in theater?

Well, it began with my parents. I was in a small college [Principia College] in Illinois, not doing very well. So, my parents, a military family, kind of pushed me into acting. They figured that maybe I had a certain inclination for it. [So] I began to do a lot of theatre. And there [was] the Pomeran [family] who had the Gateway [Playhouse] summer theater in Bellport, Long Island, where I did a lot of theatre. I did like three or four or five seasons of ten plays a summer. Then I went up to New York to study at the Neighborhood Playhouse.

Your dad was an admiral?

Well, he retired as an admiral, but his active rank was captain. He went to the Naval Academy when he was 16 years old. But since seeing my father’s people, I always like to tell it, not that it means anything, but they were southerners, but pro union. And my grandfather’s given name on his birth certificate was Abraham Lincoln Duvall. They were really pro-Lincoln.

I’ve read that when you moved up to New York, you roomed with Dustin Hoffman, Gene Hackman, and James Caan?

No, not Gene Hackman and not Jimmy Caan, I roomed with Dustin Hoffman and my brother and some others. We were all together up there, but eventually I kind of lost contact with Dusty and became friends with Jimmy Caan. I would go to California and spend time with Jimmy and stay with him out there. He let me stay at his house during many, many journeys to California. And every time I passed that house - he lived on Sunset - I say, ‘There’s Jimmy Caan’s house that he sold because they wouldn’t let him have a tennis court.’ (Laughs) It sold for like 30 or 40,000, now it’s 30 million, that house. So, Jimmy stayed in California, but I didn’t particularly want to stay out there.

What do you remember about rooming with Dustin?

Dustin used to cook. He was a good cook. As young actors we were definitely hand to mouth, you know. But it was okay. Dustin, he got more women than Joe Namath. I don’t know what he would do, he’d read poetry to them or something. (Laughs)

What was it like coming up in New York City in the 1950s?

We were always dreaming about what could happen, before these things took form as a reality. You know, we were always dreaming, talking about what we were going to do, what we weren’t going to do, what we liked, what we didn’t like, you know. I helped Dustin Hoffman get his first part on Route 66, or one of those shows. And then when he got The Graduate, it was like, like the old days of movie stardom. He just went into orbit.

I had lots of jobs. I had night jobs and day jobs. I remember I was delivering lady’s garments in the middle of the night, the night shift. I remember I was walking to work one night, I just turned around [and] walked away, and I never went back. I had lots of part-time jobs … delivering messages for a dollar an hour and everything like that. I had a job at the Post Office, [in the Broadway district] but after six months, I quit. It was a great job, but I knew that if I didn’t quit, 20 years from then I would still be doing that job. So, I said, I want to be an actor, I don’t want to work in the Post Office forever.

Brando was like our king. I can remember sitting in Cromwell’s Drug Store at least a couple times a week, me, Gene Hackman, and Dustin, and we’d mention Brando’s name 25 times. He was like ‘the guy,’ at that time.

When you were starting out, there were a lot of other young aspiring actors, hungry for that coveted break. A number of them became very successful. At the time, could you foresee any of them becoming the stars that they became?

Yeah, especially Dusty, I said [at the time], ‘I think this guy belongs in this business, he’ll make a mark.’ I saw him do a play called Eh? Off-Broadway, I think that Alan Arkin directed it. And Dusty was terrific. It was like he was a fifth Beatle. And I sat there, and it was a small theater, and I was laughing so hard, he was almost breaking up, he couldn’t do the part himself, ‘cause I was laughing so hard off-stage. But I always thought that Dusty had the stuff to do it, and he eventually proved it. When I met Jimmy, he was already on his way.

You and James Caan have stayed close friends.

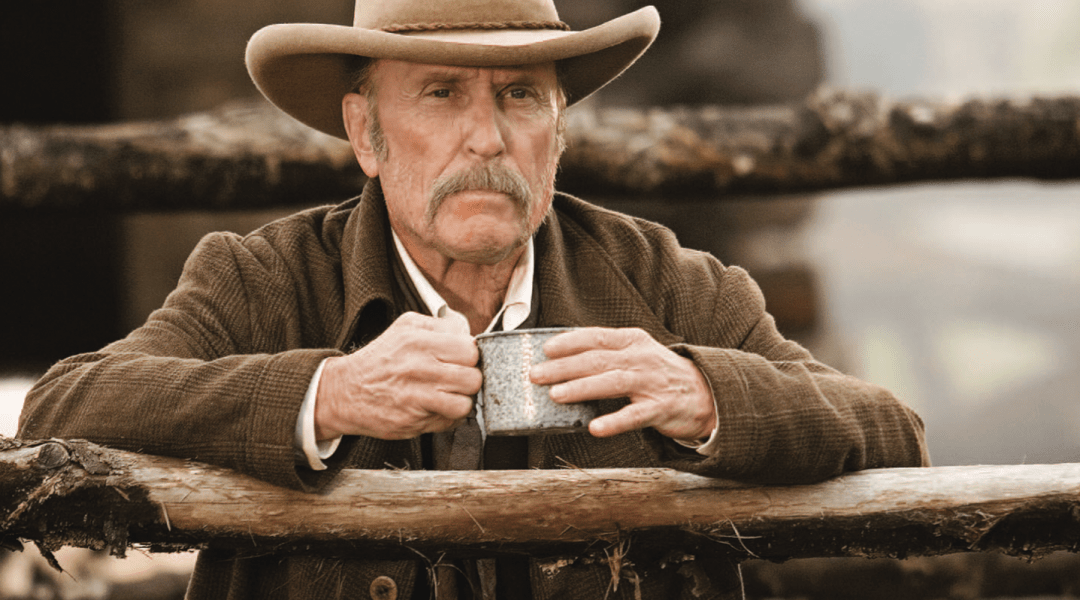

Yeah, he’s a special guy. Special guy, very talented, special guy. He’s into hobbies, we call him all-state everything. Anything he picks up he looks good at doing. You know, whether it be rodeo, or golf, or whatever. But I always tell him, ‘Jimmy, no matter how good you get at roping, rodeo, it’s pro-am.’ “No, no, no I’m a professional cowboy,” he says. I say, ‘No, no, no Jimmy, it’s pro-am.’ He didn’t want to accept that reality, you know. But I’ve known him a long time and he’s a special guy. We call up, we argue, this and that, like brothers.

Are you still friends with Gene Hackman?

No. I am not saying we’re not friends, but I haven’t talked to him in a number of years. I think that he still lives down in New Mexico somewhere.

Your breakout movie role was as the recluse Arthur Radley aka Boo Radley in the 1962 iconic film, To Kill a Mockingbird. You were 31 years old. Had you read the book?

Oh yeah, of course! I remember when I went to do it, I got a telegram from the lady [Harper Lee] who wrote the book that said, “Hey Boo”. It was nice. It was kind of a nice family thing. It was nice to have Horton Foote [screenplay writer] around when we were doing things, because he was very supportive of everything you might do. He was terrific, you know. He had seen me in [his] play called The Midnight Caller [1957]. He came with Kim Stanley and his wife and it really hit. I think I hit on something that was valid and they saw it and they remembered me when it came time to cast To Kill a Mockingbird.

Is it true that you were offered Roy Schneider’s part in Jaws (1975), but turned it down?

Yeah, I was yeah, way back. I wanted the other part [shark hunter Quint], played by the British actor, [Robert Shaw]. But I was too young.

You starred in The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather II (1974) as Tom Hagen, the Corleone family lawyer. That role earned you a Best Supporting Actor nomination at the BAFTAs, Academy Awards, and National Society Film Critics. A well deserved honor.

That happened to me twice. The Godfather and Lonesome Dove [1989 TV Mini-Series] were the two times that I figured I was in something special. Yeah, definitely. It was great being in those, you know, with Francis Ford Coppola and everything. It was great to work with Coppola, just terrific, the best.

Do you have a favorite of The Godfather series?

Well, they were both pretty well done. I sat down at the beginning of watching Godfather II, several times in my life, and I said, let me just watch five minutes of this, and I can’t help but watch the entire film. It’s so well done.

What did you think of the third film?

It was okay, I guess. It was okay, yeah. I didn’t want to be a part of it.

You play a lot of characters that are loyal, sincere, and no nonsense. Are these attributes that you generally value in yourself, that you look for in the characters that you play?

I would say so, yeah. Yeah, you try to parallel from your own experience what the script calls for. And you try to do it as honestly and as truthfully as possible.

How did you handle the fame and notoriety that came along with being a successful actor?

Well, you know, it was always enough to be flattering but not so much to be a nuisance. I wasn’t plagued in airports like other actors. It was never overwhelming, it was just enough.

Early on in your career you guest starred in a few episodes of the CBS show Route 66. Did you know much about Route 66 itself when you were doing the show?

No, no, other than just the stories, and the myth, so forth. Actually, Route 66 goes right by our farm here in Virginia, goes from Washington, DC due west.

That is actually Interstate 66, which goes from Virginia to Washington, not historic Route 66

There’s only one Route 66.

It can be confusing, but Historic Route 66 begins in Chicago, Illinois, and runs to Santa Monica, California.

I had no idea that, that was there.

Growing up did your parents take the family on road trips?

Yeah, we did, being a military family, we drove to different places, yeah. My father used to smoke, and I used to get carsick from his cigarettes. That I remember. Then he stopped smoking after a while.

Internationally, people come to drive Route 66 and seek the “golden age” of American culture and road travel. What do you think draws people to seek out the vintage period of America’s history and culture?

Well, for whatever it has to offer, Horton Foote, the great Texas playwright, always spent time in New York riding up and down. He said, ‘Many New Yorkers do not know what goes on beyond the south Jersey Shore.’ That’s true, you know, there’s a lot out there. There’s a lot out there that’s pretty interesting. They call it flyover [country], a lot of people kind of look down on all of those people. And they can be very bright, bright people. It’s all part of the tapestry of America, you know.

Would you consider yourself a nostalgic person? In that, do you ever reflect back to the past, to the heydays so to speak?

Sometimes I think back, some. I try to live in the present and to look a bit to the future. But yeah, we always look back a little bit, yeah for sure. I try to be as optimistic as possible. You can’t help but think about the past, but the past is very fleeting, memory-wise, you know.

Having lived through the 50’s and 60’s, would you say those periods were the golden age for America?

Nah, it’s just as good now as it always was. Do you remember Burma Shave?

Yeah! I love Burma Shave signs.

I was a kid, and you know, you don’t see that anymore. Nothing like that. It’s like those were more innocent times. The innocence of then was … some of that was kind of valid. Back then you took long train rides, or you took long automobile drives across the country or halfway across the country. That’s how we traveled west to my uncle’s ranch in northern Montana, by train, at the end of World War II … right at the end. So, I remember that. How you traveled and what you saw as you traveled was very different than today.

You wrote, directed, and starred in the 1997 American drama film, The Apostle. It went on to be quite successful, but you initially had difficulty finding support for it and ended up investing your own money into it.

My own money, yeah. But I got my money back. I broke even on the money, which was good, but it was difficult getting it made, yeah. I felt that the subject … very often in Hollywood, and other places, they made caricatures out of these kinds of people. Whether you agree with them or not, you can’t make it that.

Where do you stand in regards to Christianity and religion?

I definitely do believe in Jesus, the works of Jesus Christ, and yeah, I would consider myself a Christian. We were brought up Christian-Scientists. I don’t particularly go to church, but I spend a certain portion of each day in my own kind of meditation, and you know, whatever that means, and whatever that is.

You turned 90 this year [2021] and have had a hell of a run. If you had the opportunity to go back to 1955 and talk to a young Robert Duvall just starting out, what, if any, advice or thoughts would you share with him?

I don’t know! I don’t know what I’d have to say. Maybe to do the same things all over again. I was in two epic things: Godfather and Lonesome Dove. I went into the kitchen one day on Lonesome Dove, and I said, “Boys, we’re making the Godfather of westerns.” Which, I think we were … It was those two films that I felt … this is really something special. But you know, there’s always somebody out there who doesn’t like you. No matter what you do, there’s always somebody that doesn’t like you, even if you do good work. So, it’s a dog eat dog profession.

You were slated to receive the prestigious lifetime achievement award at one of our favorite museums, the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, which is a great Route 66 town. But due to Covid, the awards got cancelled.

Yes, exactly.

What does that recognition mean to you?

I mean, to represent, not to become that, but to represent [cowboys] in a valid way, in a respectful way, you know. To get positive feedback along those lines from guys like Buster Welch, my friend … he trained all the cutting horses on the King Ranch, was twice world champion cutting horse rider.

I’m not a cowboy, but I can represent what he is, and in a pretty valid way.

What do you think it is about cowboy and the western heritage narrative that still interests people today?

It’s always a prominent thing, in movie culture and American culture, the Western. Having spent time on my uncle’s ranch at the end of World War II, as a kid, it kind of inundated me with a sense of some kind of western culture. I didn’t know that I was going to be an actor at that point, but you know, I eventually became an actor and I drew stuff from my uncle’s ranch and from, you know, certain links to my mother’s Texas heritage.

People in Europe love westerns. And they have the Atlantic Ocean that faces them. You know, in our country, we expanded westward, our civilization in the United States was always what’s next? What’s beyond those mountains, what’s beyond those plains? It was always looking westward, across land, across terrain, topography. So, many westerns, they romanticize cowboys, but it wasn’t all roses with those guys. You know, it’s a tough life, but I guess they love it.

Do you have any favorite western films?

The Searchers is not one of them. I’ll sit down and debate that with anybody. I don’t find The Searchers that great of a movie. It’s filled with weaknesses. I liked Dances with Wolves a lot. I liked what Kevin [Costner] could do. I have friends who didn’t like the movie at all, but he accomplished certain things, and they used real Indians! They used real Native Americans, which was great!

What made you decide to buy a farm in rural Virginia?

Well, I bought one over here because my brother was my lawyer at the time. He passed away, but my dad was from Virginia and my brother lived here, so I kind of gravitated here and I, you know, I feel at home here. My wife is from Argentina, and I think I’ve told you before, but she loves Virginia and says for her, Virginia’s the last station before heaven. So, we like living here, it’s a nice place and yeah, so we have a nice life between us.

When you look at all that you have accomplished in your career, have you met all of your goals?

[As a young man], I suppose that you don’t know what you’re hoping for. But yeah, things come in segments: military parts, western parts, yeah. There are things, a few things, that I would still like to do, but it’s always a matter of raising the money. So, you know, maybe there’s a few more left, maybe not, but I feel like I’ve had a good career through the years, and I feel grateful. I have gratitude for things that have come my way.