Congrats on your show! It’s incredible. What drew you to the role of Eli McCullough on The Son?

Oh, thank you! That is very encouraging to hear. The story by Philipp Meyer was one that I knew, and I had read the book.

It came out of left field really. Two years ago, I was headed to Russia to make a movie which fell apart, which is quite normal these days, and I told my agent that I wanted to work and he said ‘well, you’ve just been offered The Son.’ I knew about the book and they sent the first five episodes [scripts] to the house that night. I read them, and I said, “I’m in.” I’d love to play this role. It was very instinctual, and a very immediate response. There was no second guessing. I grew a beard, I just thought that a beard would be a good transformation for the [patriarch] of the family. Luckily, I grow a good beard. I did the accent, went straight to work on it ... that was a challenge.

I read that you reached out to Texans like Matthew McConaughey to help you master the Texan accent? Is that true?

No, I’m a huge admirer of Matthew’s work and his Texan musicality and his bravado of performances, but no, I didn’t reach out to Matthew. He’s quite the hero there. But no. I have a wonderful dialect coach and there was one on-set. You know, I just immersed myself in the Texan dialects and listened to many senators actually. Ted Poe was one of them. I listened to him and to Waylon Jennings. I listened to Willie Nelson. You just immerse yourself, and then of course, when you get there, you’re surrounded by these magnificent Texans of great spirit, and that was it really.

You became an American citizen in 2004. Do you still ascribe strongly to your Irish roots, or have you been in America for so long now that you consider yourself more American?

I think I’ll always be an immigrant at heart, and that heart and soul, and the fiber of my being is intrinsically Irish. And everything I do stems from an Irish heartbeat, but America’s my home and I’m an American. I’ll probably be scattered on American soil. You know, I dreamt of America as a young lad watching movies as a teenager. It was exhilarating, intoxicating, mystical and magical, and other worldly. As that saying goes, ‘a man becomes what he dreams’ and I managed to find my way to America.

I was so blessed by getting Remington Steele and I was very conscious and fully aware that I was going into the fabric of American society. I was very aware that I was being accepted as an American and that was golden to me. It meant that I could have a career in America. It meant that ... when I was an actor in Ireland, when I was an actor in England where I trained as an actor, I was always being cast as the Irishman or the mid-Atlantic American. I found it hard to find English roles because they were given to the English actors, so I was a little bit on the sidelines fighting my way to center field. So, when I got to America, I felt like I could fly. I thought that I could play anything. I felt that I was accepted and I didn’t feel such a stigma about my own musicality of a voice, so there you go. Remington Steele gave me wings to fly and I held on with both hands. And then of course the whole story of Bond came along, and then it disappeared again, and I carried on working in America.

I’m very proud to be an American citizen. I love the country. I love the people. I love the spirit of it, even in its mangled state right now.

You’ll be 66 years old in May. Has it been difficult getting older in Hollywood?

I think a lot of it has to do with my Irish Catholic faith, being brought up in the Church and having some philosophies of life added to that, just being as tough as old boots really, because you have to be as tough as old boots to be an actor. I wanted this life, I wanted success, I wanted to be famous, I wanted to be in movies, and I got it, and then when you get it, what do you do with it? Well, you just get on with it. You keep going out there, throwing the line out, and fishing. You want to get better and to sit in the saddle strong, and stay challenged, so all the nonsense of crisis really has escaped me. I’ve just had such a great time doing it all, and there’s a wonderful beauty of mystery to it.

I came into my 50s and it was ... 50 was fine, and then in my early 50s, there was a little bit of turbulence, nothing to write home about, just a questioning of the doubting, and that time past, time present, time future, and so I think that lives with you always really. Ultimately, dealing with death ... you’re dying, not to be morbid, but I think when you do face that, you have a certain strength within it, and especially being an actor, it’s such a precious game, so I can’t say I’ve had any crisis, not really. I mean, I’m aware that I have a number of years notched on the belt at 65, but it feels good, it feels strong, it feels powerful, and at the same time, I feel like I know nothing, I feel like I haven’t done enough, and there’s that kind of gasp in the night sometimes, when you go, ‘Oh, what have I done? What am I going to do?’ And you kind of take another breath quietly and get over it, and get on with, it and just enjoy it all. Because my job is to entertain.

You were quite young when your dad walked out on you and your family and disappeared from your lives. Do you think that his abandonment has impacted the type of father that you’ve been to your children?

I think growing up without a father has given me a resilience in life. It’s given me ... somewhere deep down, buried in my heart, a sorrow and a sadness that I never had a father, that I don’t, and have not had that touchstone in those initial years of life, to have the vocabulary of being a father, of understanding the relationship as a son with a father. And I think there’s a melancholy there that I shall carry forever. I [do] wonder [about] who he was, and how I would have been different, if he had stayed. But at the end of the day, I’m glad he ran to the hills because, you know, I’ve made myself the man I’ve become, from sheer strength of character, and at times, isolation and a loneliness. So, there’s great beauty in that and great strength in that, and great poetry in that.

When my first wife and I met, she had two children beside her, and I embraced that family. Embraced that life. She was a beautiful woman and the children, my stepchildren, were young, so I was fully aware that there was a sense of having a family, an instant family, as a young man of 23 or 24. She said she was 28, but she was actually a little bit older than that. (Laughs) So, I became a stepfather to Christopher and my late daughter [Charlotte] when they were 4 and 5 years of age.

But going back, before that, when my father left, my mother had been a constant source of comfort and inspiration, and we both suffered the consequences of the Irish Catholic closeted shaming of religion, for a family that is broken. In the early 50s, she had me when she was 19, and [my] father was a man of 31 years of age, Tom Brosnan ... He was a handsome fellow, he had great style, he had a great walk, he was a carpenter and he was an artist, and he was a great whistler. That’s as much as I know about Tom Brosnan. But he had the most beautiful girl in the town, my mother, and he was a jealous man. So I think that she suffered greatly. [Then] he left.

In the 50s, if you were a single mother, like she was ...I lived with my grandparents, Phillip and Kathleen, and an aunt and an uncle, (her sister and brother). Then she took courage in both hands, at a very young age, to go to England to be a nurse. And there was a lot of heartache in making that decision, but she knew that if she made the decision to stay in Ireland, there would be no life for her, and there would be no life for me. In church on a Sunday, they would call you out as a member of the congregation and it would be a shaming, because she was a single mother.

On the banks of the River Boyne, the church ruled your life, the church had a hold on your existence, and people would cross over to the other side of the street when she walked down the street. But my grandfather was my father, and he was a kind gentleman, and he was loved by everyone. He worked for Esso, the oil company, [as] a manager. We had a beautiful little bungalow on the other side of the river, across from the town, so I lived in a kind of bubble on my own somewhat. The aunt and uncle went off and got married, grandfather died and then I just lived with my grandmother, you know, in this kind of beautiful bungalow with a garden, an orchard, the odd cow here and there. It was ... it sounds terrible, but it was quite magical, because I had the world to myself, and I had my own imagination, my own upbringing, my own dreaming, and a longing and a yearning because I knew I didn’t have a father, and then my grandmother died and I lived with an aunt. But she was having her own family and children, this good heart that she was, she couldn’t take care of me, and the uncle couldn’t, so I ended up with a wonderful lady called Eileen. She had a lodging house in the town, and she had a son and a daughter and her husband had gone ... [they were] very very poor, and she had a lodging room upstairs, and she had these two lodgers, and I lived in the same room as them. So, I had a little bed at the end of the room, put a curtain around it, and it was a kind of a metal, iron bed with a horse hair mattress. But I was happy. I was beyond words happy.

How old were you when you joined your mom in England?

I was eleven years of age when she and I reconnected, but she would come home. She would come home at Christmas and Easter, whenever she could get away. She would write me letters every week, and these little letters would arrive, and there would be a comic book, and she’d write a letter and stick money, with a piece of scotch tape, on top, and I kind of got on with my life and waited for her to send for me. And she did eventually, but that particular time living with Eileen was just the deepest happiness of those childhood years, because I was surrounded by ... I was in the town, and I had kids to play with, and there were adventures, and cowboys and Indians, and going scrumping for apples in the orchards. I had a dog and there was the river right by us. You could swim in the river. So, there you go.

I left Ireland on August 12th 1964, the same day that Ian Fleming passed away. That was it, and then a new life began. I got off the plane, I was an immigrant, I was a fresh country-faced boy of eleven years of age, and I was with my mother. It was a lovely summer day, and beside her was a man called Bill Carmichael, and he became my stepfather, and he was a kind-hearted Scotsman. He was a working man, he was a panel beater, he did body work. He was from Glasgow, and that day, that morning, my life just became otherworldly. It was joy, it was happiness.

When you first immigrated to America, where did you begin your journey?

I left with my late wife, Cassie, to go to America in ’81 and we went to Los Angeles. I had never been to America [before that].

That was quite a gamble!

Oh, we threw the dice! I was an actor, obviously by this time. I’d been in the theatre, did a West End production of one of Timothy Williams’ last plays. Then I got an American miniseries [1981] called The Manions of America which was about the Irish potato famine. It was a six-hour show with Kate Mulgrew, and Cassie said, ‘we should go to America when the show comes out’ and I said, ‘well, we don’t have the money’, we had just bought a house in Wimbledon. She had just worked on a James Bond movie, For Your Eyes Only, and so the proceeds from her movie and the miniseries, Manions of America, we bought this house. And she said, ‘no you’ve got to go. So, I went to our local bank manager and borrowed £2,000 and we hopped on a flight to Los Angeles. In those days there was a guy called Freddie Laker, he was an Englishman, and he had three flights, they were about $50 ... bring your own sandwiches ... and we got on the back of the plane. We stayed with an agent that I’d just gotten a week before, an English guy, and we stayed there in the heart of Hollywood, in the shadow of the Chateau Marmont.

We got into L.A. that morning, so excited, Cassie and myself, ravenous, there was nothing in the apartment to eat, we walked up the road and landed on the Sunset Strip, and we went to a place called Schwab’s, and that was my first breakfast in America.

Wow, you remember where you took your first breakfast, all these years later?

Well, because you know when you’re on the cusp of something great. I wanted America, I wanted it so bad, with every fibre of my being, and I was also in the hole for £2,000 (Laughs). I rented a car from a place called ‘rent direct’, and it was a lime green Pacer, with a wing kind of hanging off, and a cushion on the seat because the springs were going up through your ass, and I went on my first audition, I drove across Laurel Canyon, and the audition was for Remington Steele.

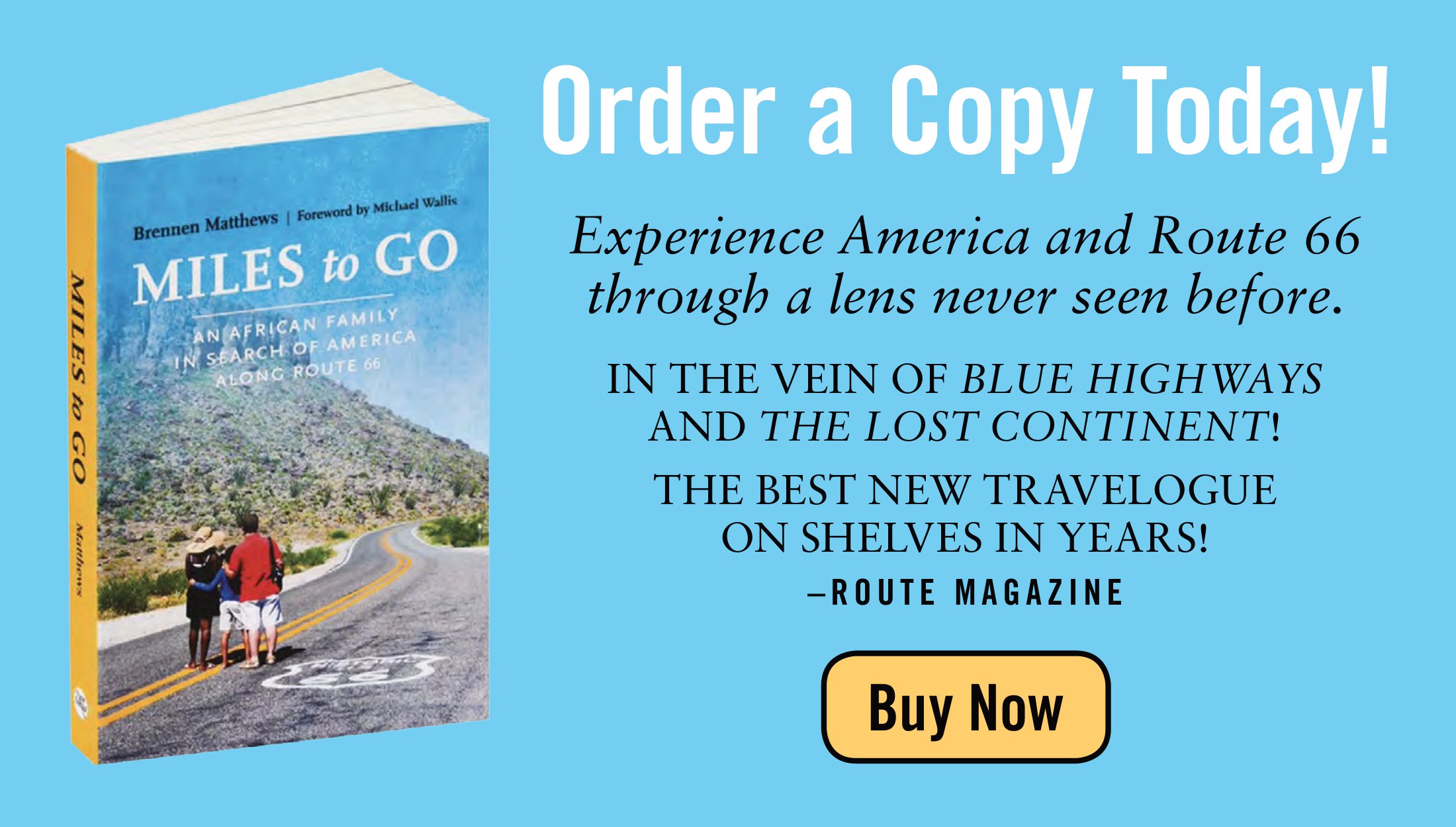

I know you travel a lot, but do you and your family enjoy road trips?

I have never done a road trip, no. But my life has been a road trip, in the sense that the travel and the countries that I’ve been to ... It was one of my dreams actually, to get a motorhome in the early 80s and do Route 66, but I was working so hard, and when I wasn’t working hard, I was working hard looking for work, that I never did the road trip.

You grew up enamored with Westerns and cowboys and Indians ...

There were two cinemas in the little town that I grew up in, one was called, The Palace, [the other] was called The Lyric. The Palace was the closest one to my grand-mother’s house, so I would go to the pictures, as we would call them, and it was cowboys and Indians. Cowboys and Indians and British comedies like Norman Wisdom or Mother Riley. So the cowboys and Indians were deep in the fabric of the Irish heartbeat, and growing up with my grandmother on the banks of the River Boyne, every springtime this family of tinkers would come around, and she was a gypsy, and she had two sons ... she had a beautiful horse and cart and she would mend the pots and pans of my grandmother and her sons ... they knew all about making the best bow and arrows, catapults.

So, what I’m trying to say is that I was always an Indian. (Laughs) I was always the Indian, however, when I got to London and I discovered the movies, Clint Eastwood was my hero. So, there you go, roundabout story playing the cowboy.

What do you think is so appealing to Western Europeans when they think of Route 66 and the 1950s era of America?

I think it’s the pioneer spirit of the people, because it was a virgin landscape in many respects, and there was such an innocence to life, and so the culture was discovering its own being and self, and the automobile created such an accessibility to the land, just like the railway came across the nation, and the music. I think it goes to the music of that age. Elvis, the romance of travel, the romance of falling in love with girls from another state, or just down the road, and then wanting to get out of that place to go find the world. When you build a road, it lets the world in, and that beautiful car with just four wheels and some kind of engine and gas in it, gives you a lot of freedom, and a lot of dreaming, and I think, you know, just the road itself has such a huge breadth of beginnings of people’s lives. England is quite small and intimate, and just the vastness of America.

I think you need to get on the road and do that road trip that you’ve been dreaming of. It sounds like it's right up your alley at this point.

Yeah, I think it could be, Brennen, I think it could be. My wife and I are almost empty nesters. Paris, our youngest, has turned 18, and Dylan’s off at college at USC, and Paris is going off to college soon. My eldest son has got his family, and my stepson has got his life in England, so Keely and I have been tripping the lights on down the road happily so for twenty-five years, as husband and wife. So we do talk about it.

I’m going to carry on being an actor, and my painting has become more pronounced in my life, and I’d like to get better at that, having exhibits and, you know, we talk about my going off and doing character roles in movies here and there, and she’s a great lady, she’s my North Star and has given me wings to fly in this career, and traveled with me hand in hand across the world, especially in the days of Bond. She’s made the most beautiful home for our sons and myself.

We talk about just getting up by ourselves and traveling, which we’ve never really done, it’s all because of work, it’s because of a movie. We have a home in Kauai, Hawaii, which is a really small little bungalow homestead, but it sits on 5 acres on the water’s edge, and she’s a great gardener, and from sands and weeds she has made a landscape of 300 coconuts and an orchard and banana groves, she’s a powerful gardener and writer, and she’s just made her own first documentary film called Poisoning Paradise.

Who is the funniest actor you know?

Robin Williams, bless his heart.

Tell me more.

There was such a humanity, and kind of mischievous, devilish, outrageous flair of kaleidoscopic thought process, that you just didn’t have time to breathe with his comedy. He just came at you like a freight train of ‘I want to please you’. He just loved to turn people on, and he turned the world on in the most glorious way.

When I got Mrs. Doubtfire, there was a time I said to my agents, I said ‘look, I’m a working actor, I just want to work with good people, I just want to pay the rent.’ And Mrs. Doubtfire came along and whoa boy, the script was so well written, you could feel the movie, you could sense the movie. I flew up to San Francisco on a spring morning, I got there and they said, ‘do you want to meet Robin?’ and I was so excited to meet the guy, I was so thrilled to have the job, to be with Robin, to be with Sally Fields, I went into the makeup trailer and there was Robin Williams sitting in the Hawaiian shirt, with cargo pants on, and Ugg boots, but his arms, his big hairy arms hanging out, just Robin Williams. However, he had the head of Mrs. Doubtfire. So there he was, it was the head of Mrs. Doubtfire and he said (in her over-the-top voice), ‘oh Pierce, oh you’re so handsome, oh come here, give us a hug, you lovely boy you’ and I said, ‘so good to see you Robin. Then he said (in a husky, manly voice), ‘hey dude, I’m so glad you’re here man, so glad you’re here, it’s good to see you Pierce, good to see you. Thank you for being here.’ And I said, ‘oh I’m thrilled to be with you man, it’s just great to be with you.’

I never really worked with Robin Williams [on the movie] because every day I went to work he was Mrs. Doubtfire, and it wasn’t until the end of the movie that I saw Robin and sat with Robin, and hung with Robin, because I’d go to work and he’d be in the chair from four in the morning. We’d do a full day’s work, I’d go home, he’d go home, we’d all go home ... so there you go, that’s my Robin memory. It deeply saddened me.

It was very surprising, and very sad.

You have so much going on, what other projects should we keep an eye open for?

Well, we’ve optioned a book called, Girls Like Us, and it’s Carole King, Carly Simon and Joni Mitchell. The piece is a broader version and a kind of template, but really the story of women in music and the relevance of the song writing, and their own coming-of-age in a society that is very male dominated, so it’s not just those three ladies, it’s a broader neck. It’s women in music.

We’re looking at this as a documentary, we’re looking at this as a four-part series.

For TV then?

For TV, yes. We’re working with a wonderful director who did a magnificent documentary on Elvis, and he did one with Bruce Springsteen. We are fledglings, we like the documentary format. Keely started as a writer and producer with her own TV show, a gardening show, called Home Green Home. Really, kind of gave up her career to be a mother, to create this life for us, and she’s the most magnificent mother, incredible lady, her courage, her strength, her stamina, and her beauty. Yeah, the two of us have got plans to work.