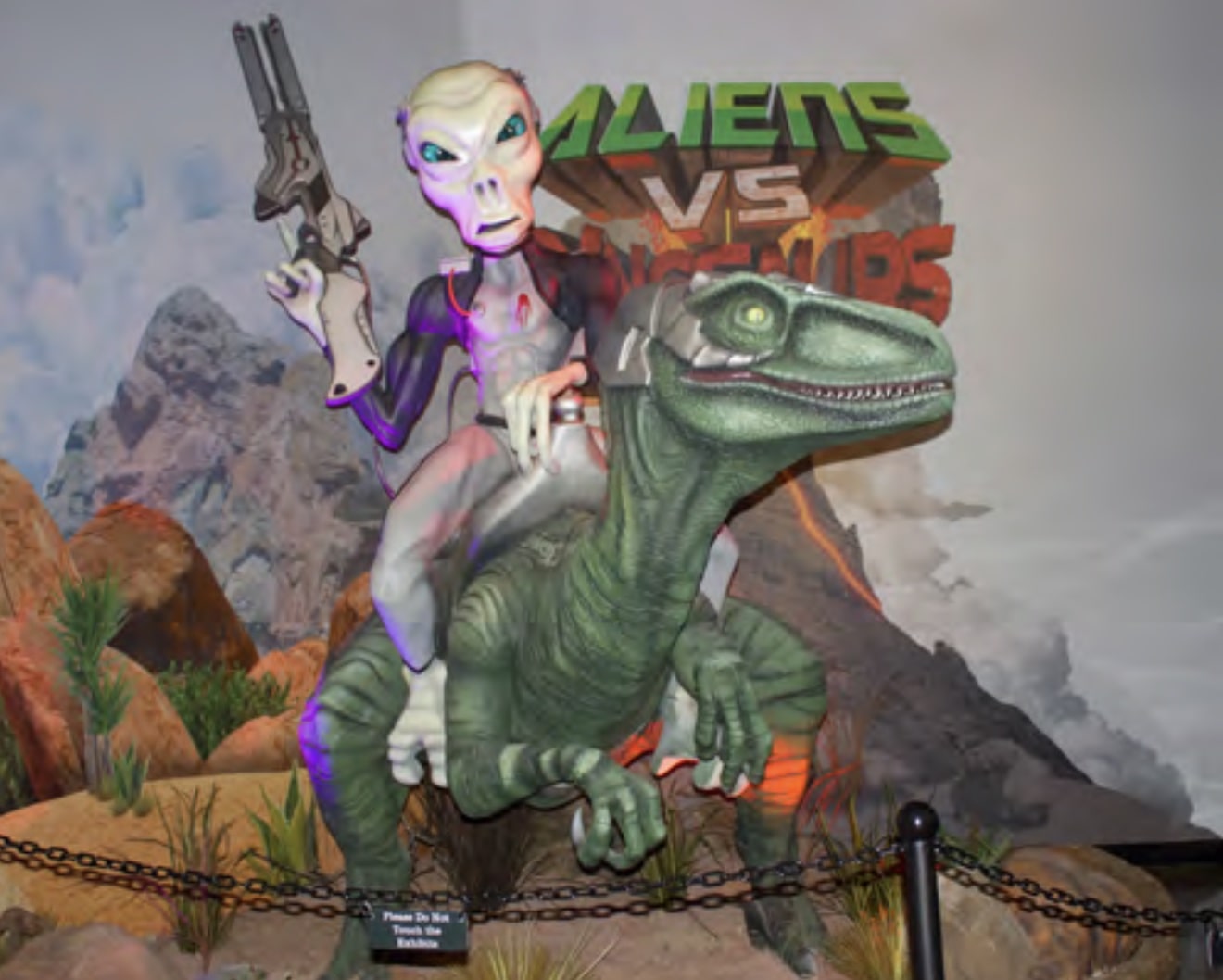

With its sprawling gift shop and 12,000-square foot museum, The Thing could be considered one of America’s most strange and random pit stops. In 2018, the attraction received a major upgrade, acquiring a new conspiratorial element to complement the mystery and ambiguity of its main attraction. Now, visitors to the attraction are taken through a tour of America’s possible past—one defined by dinosaurs and aliens, which as this peculiar exhibition claims, took part in some of the most important moments in world history.

“We kind of married the idea and notion of dinosaurs and aliens and created a storyline and actually created the theme, if you will, of aliens traveling to and finding Earth and integrating with the dinosaurs, basically enslaving dinosaurs,” said Kit Johnson, Director of Operations at Bowlin Travel Centers. “And the aliens, when they came, were of two descendants: one a good guy tribe, if you will, and a bad guy tribe. And they enslaved dinosaurs, until at some point, they were unable to accomplish that in total because of T-Rex and his power and, I guess, independence. And then, the destruction of—the big meteorite event was not really that—it was a blast coming from an alien spacecraft that destroyed all the dinosaurs. And then aliens began integrating themselves into society from that moment on and have had a huge effect on the history of our world—either good or bad. And there’s a ‘What if?’ theme. What if aliens actually did integrate with society? What if they really did have a lot to do with the way our history played out over time? And the last exhibit, of course, is The Thing, which ties into this theory of aliens’ involvement with humanoids, and The Thing actually being that key that ties it all together.”

But before these extraterrestrial and primeval speculations came to fruition, The Thing, a mummified humanoid figure reminiscent of what Indiana Jones might find in some mythological ruins, stood alone in the barren Arizona desert. One of the last of its macabre kind, The Thing is rooted in America’s carnival tradition, hailing from the long-lost art of “gaff” creation. While no one knows exactly when and where gaffs were created, their genesis is often attributed to circus mogul P.T. Barnum, who began his carnival career by showcasing human oddities, such as the alleged 161-year-old nurse of George Washington.

As Barnum’s traveling circuses began to dominate the realm of 20th Century entertainment, a crafty, eclectic man named Homer Tate was inspired to take up the gaff trade— and thus, The Thing’s journey began.

The Black Sheep of the Family

Considering the morbid bizarreness of The Thing, it’s no surprise that its creator was as eccentric as the spectacle itself. Sometime during the early 1940s, Tate had the idea to take his artistic talents to new heights. Inspired by the popularity of sideshows during the era, Tate decided to profit off other people’s foolery in an ingenious, rather resourceful way.

“[The Thing] was created by Homer Tate in 1950, and he was—well of course, everyone involved with The Thing was an interesting character,” said Ken Smith, co-founder of Roadside America. “He was a papier mâché artist, and he was actually kind of like a Norman Rockwell. He would do these very delicate, sort of whimsical themes of domestic life and very heart-string-tugging things. And for some reason, in the 1940s, he sort of dumped all that and started doing these monstrosities. He was an interesting guy because he would use papier mâché, but he would also incorporate biological pieces. He would go out into the desert and find dead animals, and he would use, you know, skin, hair, nails, claws, all kinds of things that he would incorporate into these creations of his. And, he ran a curio shop in Phoenix, and he had a catalogue to sell these things to sideshows, and they would be shown at carnivals, they would be shown at county fairs, etc... But Homer Tate is very well-respected among people who collect these kinds of things.”

Not only was Tate’s cadaverous enterprise quite unusual by ordinary standards, it also deeply offended his highly religious family. “They were Mormons, and he was known as the black sheep of the family because he was making these monstrosities,” Smith said. “And when this happened, he was like 70 years old. I mean, he wasn’t like a kid, you know? And the story is—who knows if it’s true or not—they got into his curio shop in Phoenix and destroyed all of his stuff because they found it sacrilegious and disrespectful.

So, there aren’t very many pieces of his that have survived, but The Thing is one of them, because he had sold it before that.”

The Thing Finds a Home in Arizona

While Tate is credited with the creation of The Thing itself, an attorney named Thomas Brinkley Prince was responsible for bringing the famous gaff to Arizona. Originally born in Texas and raised in California, Prince ended up in the Grand Canyon state during the 1930s as a student at Arizona State University. He then went on to the University of Arizona’s College of Law while his wife, Janet Prince, supported his studies by working at a local clothing store for 35 cents an hour. After obtaining his law degree, Prince bounced around the Phoenix legal scene for a number of years, even briefly serving as a prosecutor in the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office before World War II began. Over the course of the 1940s, he and his family made their way up to Seattle where Prince worked at a local law firm while also running a pool hall on the side.

As life during wartime passed, the 1950s brought a breath of rejuvenation to the county, prompting many Americans to create their own new beginnings—Prince included. He decided to ditch the law profession, which he found “stuffy,” and migrated his family back to the scorching Mojave Desert of his home state, where he planned on constructing his own house of curiosities off Highway 91— between Barstow and Baker, California. Somewhere along the way, The Thing entered Prince’s possession, and according to the documented account of Janet, he bought the faux mummy off some traveling salesperson for fifty bucks. When Prince was forced to relocate his roadside attraction after losing his property to interstate highway expansion in 1965, the family elected to return to their roots in Arizona, building a new emporium near the newly minted I-10 with The Thing as its centerpiece.

“[Prince] owned The Thing, and by the 1960s, he brought it with him back to Arizona from California,” explained Smith. “When he built the attraction, it was actually sort of his version of a carnival midway, or a dime museum. He built it that way where you go in, and there’s all these exhibits that you would go through, and then you’ve got The Thing. Of course, these exhibits were just these everyday items that he would give these fanciful names to, which is sort of what P.T. Barnum did with the dime museums originally. So, that’s the way he built it back in 1965, it sort of hearkens back to that earlier sort of attraction where he turned what was a mobile attraction, which would go around to fairs and carnivals, and made it a permanent roadside attraction out in the Arizona desert. And he did it on an interstate, which was another odd thing, because we associate most of these roadside attractions with places like Route 66 and places like that, but The Thing has never been on a road like that. It’s always been on that interstate exit.”

While no one knows exactly why Prince decided to purchase this ghastly piece of memorabilia, the motives behind his acquisition are irrelevant when you acknowledge The Thing’s decades-old popularity and Prince’s business savvy. It’s clear his decision paid off. However, Prince’s time as owner of the roadside attraction ended in 1969 when heart difficulties and a series of strokes got the best of him. After her husband’s passing, Janet Prince assumed responsibility of The Thing, but with her life partner gone and only child, Michelle, attending Stanford, the isolation of living alone in a single trailer behind a shop in the middle of the desert became unbearable. After only a couple years of managing the business solo, Janet Prince leased the attraction to Bowlin Travel Centers Inc. and moved to Maryland, where she lived until her death in the early 2000s.

After relocating, Janet never returned to Arizona to see The Thing again, but she used the lease payments from Bowlin to support Michelle and her two adopted children. Perhaps more significantly, every year until her passing, Janet donated a portion of The Thing’s profits to support five $1,000 scholarships that she funded in her husband’s name at his alma mater, the University of Arizona Law School. Considering the countless hours that she spent all those decades ago scraping together her earnings so that her husband could get his degree, these scholarships served as Janet’s poetic gesture to continue her support of future lawyers and their dreams (no matter how unorthodox they may be). Upon Janet’s death, Bowlin officially bought out the property housing The Thing, but still maintained the kitschy atmosphere that Thomas Brinkley Prince established nearly a half century ago.

“When [Prince] died in ’69 and Bowlin took it over, they didn’t change it,” Smith clarified. “They just left it the way it was. It was the same exact way in 2016 that it was in 1965. So, that’s pretty remarkable that it lasted that way for so long. But I think the genius of Prince was that he could have opened an attraction and said, ‘Come see the dime museum!’ But no, he recognized that The Thing was the star, and that’s how he advertised [it], ‘The Thing! What is it?’ And that’s the genius of it because that’s what pulled people in. You know, he focused it like a laser beam right on The Thing. And it has survived because it [makes] money. They wouldn’t have kept it around if people weren’t [still] pulling off the road to come see [it].”

Although The Thing’s history is undoubtedly fixed in Tate’s sideshow craft, many people have developed their own theories about the object over the years. For instance, a rumor that The Thing is actually an embalmed mother and child has circulated over the years—inciting a bit of controversy in the process.

“In 2002, there was a court representing indigenous peoples in Arizona, and they approached Bowlin and said, ‘This is disrespectful. You need to bury The Thing because this is an ancient artifact,’” Smith recalled. “And they said, ‘No, it’s not. It’s really fake.’ I like to think that Homer Tate would have smiled at that.”

In terms of The Thing’s advertising presence, it’s hard to miss the many giant billboards that constellate the southwestern highway from El Paso, Texas, to Tucson, Arizona. According to Smith, even this aspect of the attraction is unique. When Lady Bird Johnson joined the Keep America Beautiful Campaign during the 1960s, many billboards across the country were torn down—and yet, The Thing’s signature roadside campaigning still thrives to this day. “It worked in its favor that it was actually the only thing out there and escaped the harsh ‘tear down the billboards’ craze that swept across America during the late ‘60s and early 1970s. You know, there were other attractions that did that, but those billboards are all gone. The Thing is sort of a unique survivor that way,” he remarked.

“What If?” That Is the Question

For an object shrouded in such mystery and controversy, The Thing is surprisingly simple in its respect. It could be viewed as one of the last remaining examples of raw human ingenuity—a one-of-a-kind relic from the days before television and internet defined society, when people were forced to rely on their own imaginations to have fun.

There’s no question that the hype surrounding The Thing is completely unwarranted. Yet, in Smith’s mind, the fact that The Thing is so laughably anticlimactic is key to its appeal.

“I think in America—we complain about it, but we like being fooled. You go, ‘Ah, I can’t believe I’ve got to pay a quarter to see this thing.’ And you go see it, and you go, ‘Ah, that was terrible.’ But you still do it anyway because, you know, it’s fun! And, certainly, The Thing never charged a lot of money. You could take the whole family back there. I say this a lot, but a good roadside attraction—it isn’t about what it is. It’s about what you remember. It’s about building a memory. And, certainly, The Thing, when you go there, you never forget it. You know, it’s always going to be something you talk about. People will say, ‘Oh, you were in Arizona! Did you see The Thing? Have you seen it? Yeah, oh yeah!’ There’s a certain intuitive genius to that, and The Thing is a great example of that.”

Since its inception, The Thing has morphed into a representation of what America once was, and perhaps what it still might be—even in the smallest sense. The attraction was born during a time defined by both creativity and change. From the days of Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement to the moon landing, the 1960s proved to be one of the most eventful, life-changing decades in American history — so why not unveil something as mystifying as The Thing to further kindle the American imagination?

For present-day visitors, The Thing will appear a little different than it did in its heyday, but the overarching theme remains the same as it’s always been.

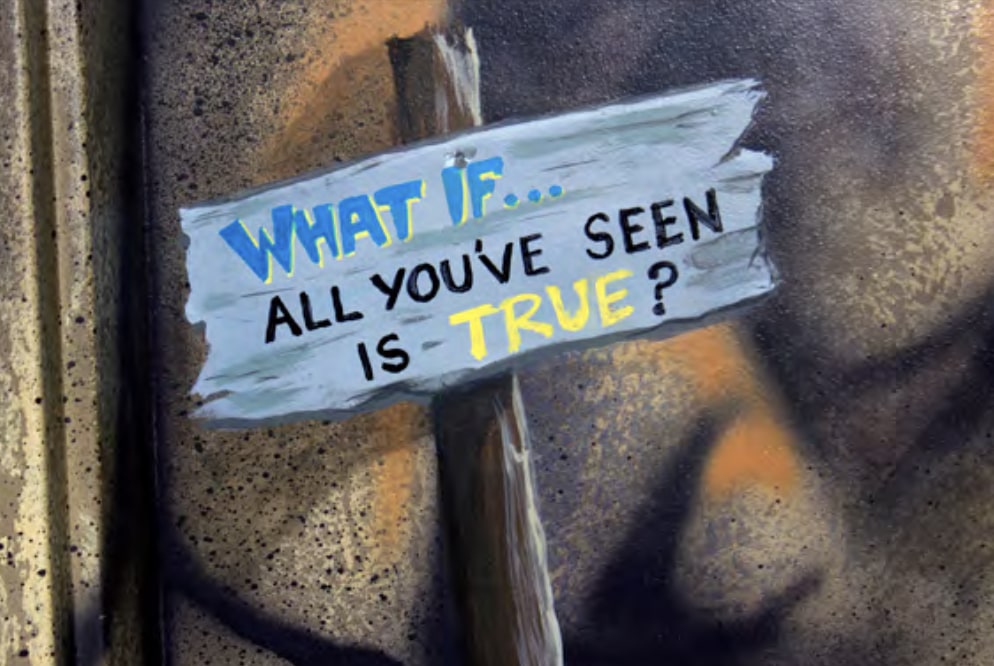

“The whole theory—the basic theme throughout the Museum is the ‘What if?’ phrase, which gives you full latitude to determine for yourself if this thing is accurate or not,” Kit Johnson said. “We have created an experience for our customers and the people that go through the Museum that gives them—it’s fun, it’s challenging, it’s interesting. It gives them something else to think about in respect to our history of the planet, history of the country. There’s an entire wall of conspiracy theories—John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the Twin Towers, Amelia Earhart, and the whole theme is, what if aliens had something to do with some of these, if not all of these events?”

Regarding The Thing’s new conspiratorial element, Kit couldn’t say for sure if he believes that aliens and dinosaurs truly had a hand in world history. “That’s up to your imagination,” he said.

Indeed, The Thing is not the right attraction for those seeking answers to the world’s greatest mysteries. Rather, visitors can expect to walk away from their visit with many more questions than answers, but perhaps that’s exactly the point. For an attraction rooted in American ingenuity, The Thing certainly succeeds in fueling the imagination and fostering creativity.

So, the next time you hit the road in the Southwest, make sure to watch out for those great big billboards plastered against the desert sky, and remember to keep your mind as open as the horizon. After all, the greatest facets of life are the ones that keep us guessing, and thinking, “What if?”